Fortitude: Standing Fast & Overcoming the Fear of Failure

By James Hickman and Brigid Calhoun

Mission accomplishment is arguably the first task of the military. It is understandable, then, that military leaders fear failure, for that is the opposite of mission accomplishment. Fear of failure can provoke a few unfavorable reactions: either fabricating a victory (lying to ourselves), quitting, or simply not trying at all. How can we avoid the extremes of foolhardy “mission accomplished” gusto while simultaneously eschewing the non-starter’s or coward’s mentality? The answer is fortitude, the cardinal virtue that involves being strong in all aspects of the human person.

How can we avoid the extremes of foolhardy “mission accomplished” gusto while simultaneously eschewing the non-starter’s or coward’s mentality? The answer is fortitude.

In our first consideration of the cardinal virtues, we examined prudence, which we named the queen of virtue, because it decisively moves us from thought to action. A simplified way to understand virtue according to Aristotle is to think of it as the disposition to achieve the mean between two extremes in action.[1]

In today’s reflection, we examine the virtue of fortitude—often called courage—the steady disposition to do the right thing in the face of fear.

In today’s reflection, we examine the virtue of fortitude—often called courage—the steady disposition to do the right thing in the face of fear. The Greek term, andreia, is usually interpreted as fortitudo in Latin, which generates the English word fortitude. Although the term courage is arguably more recognizable in the military than the term fortitude, the latter’s root offers more insights for reflection. Fortitude should lead us to remember its cousins: fort, fortress, and fortify. Immediately, we can see the military applications of the term.

Courage itself contains an essential Latin root: cor, or heart in English. Old French rendered the word corage and Middle English offered courage. The Latin coraticum essentially means “with the grasp of one’s innermost feelings.” The French expression, bon courage, expresses verbal support before or during a difficult task. In Italian, similarly, buon coraggio is often heard from one student to the next before an academic examination or in the midst of a difficult sporting conflict, such as soccer.

To maintain the breadth of meaning contained in both courage and fortitude, we will stick to the term fortitude.

Unpacking Fortitude

An English interpretation of Thomas Aquinas’s original Latin says that fortitude is the virtue that removes “any obstacle that withdraws the will from following reason.”[2] The interpretation continues: “Hence fortitude is chiefly about fear of difficult things, which can withdraw the will from following the [intellect]. And it behooves one not only firmly to bear the assault of these difficulties by restraining fear, but also moderately to withstand them, when it is necessary to dispel them altogether in order to free oneself there for the future, which seems to come from the notion of daring. Therefore, fortitude is about…curbing fear and moderating daring.”

These words of Aquinas sound very militaristic: “bear the assault,” “withdraw,” “withstand.” This is not surprising given his context living in 13th century Christendom when warfare was part of everyday life in present-day Italy, France, and Germany. But it also resonates because Thomas wrote about prudentia militaris (military prudence), or the virtue of ensuring an effective national defense.[3] In his contribution to Just War Theory, Aquinas asserted that military leaders require both prudence and fortitude.

If we wish to understand Aquinas’s fortitude in its most elemental form, we can think of this virtue as standing fast in the face of fear, danger, weakness, and/or failure.

If we wish to understand Aquinas’s fortitude in its most elemental form, we can think of this virtue as standing fast in the face of fear, danger, weakness, and/or failure. We demonstrate fortitude by operating between the extremes of foolhardiness and cowardice. To do so, fortitude relies upon other virtues like confidence, humility, magnanimity, patience, and perseverance. Aquinas wrote that “it belongs to fortitude of the mind to bear bravely with infirmities of the flesh, and this belongs to the virtue of patience or fortitude, as also to acknowledge one’s own infirmity, and this belongs to the perfect that is called humility.”[4] If we acknowledge our limitations with humility, persevere through adversity with confidence and patience, we can succeed in standing fast.

Why Fortitude Matters for the Military

Aside from enabling mission accomplishment, fortitude also shapes our character. Vulnerable leaders, unafraid of making their mistakes and shortcomings known, tend to generate followers because they exhibit a fortitude that welcomes trust. By exposing one’s weakness, one in effect telegraphs that one is trustworthy.

By exposing one’s weakness, one in effect telegraphs that one is trustworthy.

The link between character and fortitude is further exemplified in the concept of moral courage. The military perhaps celebrates physical courage more than moral courage, but both are important for service members to cultivate. Moral courage involves telling the truth, championing right over wrong, and standing up for one’s beliefs. Service members’ failures to exhibit moral courage have contributed to tragedies like the Vietnam’s My Lai massacre and the Iraq War’s Abu Ghraib prison abuse.

Physical courage can be nurtured through repetition and exposure to “what right looks like.” The military aims to achieve this through physical fitness and combat training. For example, combat arms troops undergo live fire training before deployments to build confidence and trust in their ability to stand fast in the face of danger. The military also recognizes supreme acts of physical courage in awarding the Medal of Honor, the ultimate display of fortitude through an act so brave that the will is in accordance with reason despite very strong emotions of fear and anger.

On July 22, 2021, the Pentagon announced that U.S. Army Sergeant First Class Alwyn Cashe will be posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. SFC Cashe died of wounds after pulling six fellow Soldiers and an Iraqi interpreter from a burning vehicle in 2005.

A Personal Example: 2LT Calhoun Fails Air Assault School

Hitting the mean between the two extremes of fortitude is easier said than done. As a new 2nd Lieutenant in the 101st Airborne Division, I intensely felt the fear of failure. Like many young officers, I desperately wanted to deploy with my unit “before the war ended.” I worried that any failure or substandard performance would diminish my chances of joining the battalion in its upcoming deployment to Afghanistan. I easily accomplished many tasks traditionally given to new lieutenants: taking over the battalion Cup and Flower Fund, organizing a Hail and Farewell, and briefing at battalion training meetings. But I struggled in preparing for the one task required of all Screaming Eagles: Air Assault School.

I had failed the school as a cadet two summers beforehand. Physical fitness, especially upper body strength, had never been my strong-suit. As a cadet, I failed to physically prepare for the Air Assault obstacle course – the defining requirement of the school’s “Zero Day” assessment. Cadet Calhoun failed to properly navigate a particular obstacle named the “Tough One,” which involved a rope climb that transitioned to a horizontal plank walk that ended with a descent down a cargo rope. Fear of that obstacle stuck with me for the next two years.

Haunted by my past failure, 2LT Calhoun avoided training on the “Tough One” at the Sabalauwski Air Assault School’s obstacle course. The fear of failure whispered doubt into my ear whenever I thought about how much I needed to prepare and pass the course. This whisper is known to the ancients as logismoi (lo-geez-moy), a Greek word meaning assaultive thoughts. I only practiced the obstacle course the handful of times my battalion conducted “Air Assault Physical Training” and was too afraid to seek out additional opportunities to improve upon my weakness. I settled for climbing the ropes at the gym, which were much simpler to navigate than the complex “Tough One.”

When my battalion sent me to Air Assault School, I was beyond nervous on “Zero Day.” Our class shot-gun started the obstacle course, and I began with the obstacle right after the “Tough One.” This meant I would go through the entire obstacle course first before arriving, exhausted, at the “Tough One” as my last obstacle. I tried to ignore my fear and instead focus on the easier obstacles, successfully navigating all to standard.

I finally arrived at the “Tough One,” and my confidence was high. I mounted the rope, climbed to the top, and dismounted to the horizontal plank. My internal jubilee was cut short by one of the instructors screaming: “Hey Air Assault! Get back down here and complete the rope climb to standard! Three points of contact at all times!” I couldn’t believe it. I had just overcome my biggest fear, and now I was told I’d have to climb the rope again? My heart sank. Not only was I exhausted, I was defeated. I tried to collect myself on the ground, but the fear of a second failure dominated my thoughts. I was losing hope.

When my 30 seconds of allotted rest expired, I only climbed halfway up the rope. My legs wouldn’t lift me any higher. “I’ve failed,” I said inside. With that admission, I unlocked my feet and slid down to the ground. I heard another yell from the instructor: “Air Assault, that’s a failure to complete a major obstacle. You’re dropped from the course.” After joining the other students who failed the obstacle course, the instructor gave us our discharge paperwork and told us to report back to our units. I ran to my car and drove home, crying. I couldn’t bear my failure, let alone tell my company commander about it.

My phone rang shortly thereafter. It was my company commander. He had already learned that I was dropped from the course. I cried into the phone and apologized for not coming straight to his office, admitting my embarrassment. But rather than chew me out, he listened. He told me to get cleaned up and come into his office within the next hour. I obeyed, and when I arrived in his office, he and my intelligence officer in charge (S-2) were waiting for me. I told them what had happened on the course. Together, the three of us developed a plan of action to improve my physical fitness and enroll me in the next month’s Air Assault class. My commander even shared a story of how he failed Ranger School on his first try, which provided the perspective I needed to contextualize and find the lesson within my own failure.

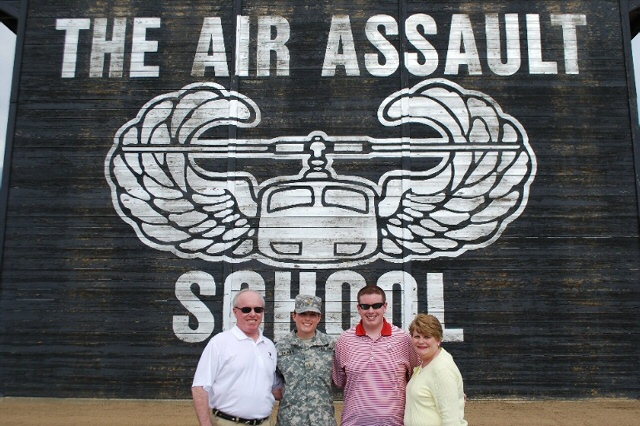

Over the next month, I overcame my fear of failure and wholeheartedly embraced the training plan. With the help of my S-2, I improved my upper body strength and cardiovascular endurance. I climbed ropes before PT, during PT, after PT, at lunch, and after work. I took advantage of every brigade opportunity to train on the Sabalauwski Air Assault school’s obstacle course. On early Saturday and Sunday mornings, my roommate and I would sneak onto the course and practice the “Tough One” together over and over. With their help and encouragement, which were instrumental in combating the logismoi, I finally passed Air Assault School on March 17, 2012.

2LT Calhoun with her family and support network at Air Assault graduation on March 17, 2012.

Better yet, my hard work did not go unnoticed by the military intelligence company commander. After observing how often I was climbing ropes around the brigade footprint, he asked my S-2 about my apparent fascination with them. She told him that I had failed Air Assault School but was preparing to return. He took note of my perseverance and awarded me with a platoon in his company a year later.

Originally paralyzed by fear of failure, I soon learned that perseverance and patience go hand in hand with fortitude. I remain grateful for this failure, and the coaching I received to overcome it. Had I not failed, I would not appreciate the truth of Aquinas’ teaching that fortitude requires us to bear bravely, patiently, and often with a measure of hard-earned humility, with our weaknesses to overcome our fear of failure.

Conclusion

As we mentioned in this article’s opening, the military’s primary mission is to fight and win our nation’s wars. That’s no small task–and most of us who have donned the uniform fear letting down our nation and comrades. This fear of failure can be paralyzing, and that is why Aquinas and Aristotle are worthy guides for producing virtuous military leaders. The emotion of fear is actually our friend rather than our enemy. The key is to embrace this fear with the proper resources: our fellow Soldiers, military doctrine, and arduous training, among other things. These resources, in effect, fortify the Soldier against thoughts and temptations of self-doubt and failure. The Soldier who doesn’t fear failure tends to be the person who either doesn’t care or doesn’t grasp the risk involved. We call him foolhardy. Conversely, the Soldier who does fear failure will either fall into cowardice or display that intestinal fortitude required to accomplish the mission, and is rightly called courageous.

About the Authors

Mr. James Hickman graduated from West Point in 2006. After serving as an Infantry officer, he completed graduate studies in philosophy and theology at the Catholic University of America and the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas in Rome. He serves the Army in the National Capital Region.

Brigid Calhoun is an active duty Army Military Intelligence officer serving as a Joint Chiefs of Staff Intern at the Pentagon.

Citations

[1] “Ancient Ethical Theory,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, February 5, 2021, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-ancient/, (Accessed March 31, 2021.)

[2] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologia (ST) II-II, Q123.A3.

[3] STII-II.Q50.A4.

[4] ST II-II, Q123.A1. Rep1.