Prudence, Queen of Virtue: Follow Me

By James Hickman and Brigid Calhoun

An old adage quips that philosophy is useless, but not worthless. It’s said to be useless because the knowledge and understanding gained from philosophy are ends in themselves – not of use for some other end. But philosophy is by no means worthless; in fact, it aids humans in the pursuit of happiness.

Virtue ethics, a subset of philosophy, has faced some contemporary scrutiny and skepticism. A recent Modern War Institute article claimed that traditional military virtues like competence, chivalry, and leadership are outdated and no longer applicable to modern warfare. The author advocated for “modern military virtues” to replace the outdated ones but failed to articulate what those modern virtues might be. We found the author’s thesis troublesome not only because he posed a problem without offering a solution, but also because he failed to define what a virtue is. Furthermore, he neglected to acknowledge the deep and rich history of classical virtue theory, which remains worthwhile for military leaders to study.

In today’s blog post, we had intended to rebut the Modern War Institute article by defining virtue for our readers and recommending the four cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, temperance, and fortitude as enduring virtues we should all adopt. However, Major Joshua Lehman beat us to the punch with his excellent rebuttal, “The Virtues We Need Are the Ones We Already Know.” So instead, we’d like to build upon Major Lehman’s argument and kick off a four-article series on the cardinal virtues, beginning today with prudence.

Raphael Sanzio (Italian: Raffaello) (1483 – 1520), Cardinal and Theological Virtues (Virtù Cardinali e Teologali), Fresco, 1511, Vatican Museums, Vatican City, Rome, Italy.

Virtue ethics is not a convoluted system that requires mental gymnastics—it is a field of study rooted in the fabric of reality.

Virtue ethics is not a convoluted system that requires mental gymnastics—it is a field of study rooted in the fabric of reality. Ordinary people, when given sufficient time to reflect, come to recognize the truth of good and evil, right and wrong, excellence and unbecoming behavior. Thomas Aquinas defined truth as the conformity of the mind to reality. In a mathematical sense, truth is “the equation of thought and thing.”[i] When what we think matches the world outside our mind, we live in the truth.

Furthermore, the cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, temperance, and fortitude have been considered the building blocks of human flourishing and happiness for over two thousand years. Just as the cardinal directions guide our physical movement, the cardinal virtues direct our actions towards good living. In this essay, we ground our understanding of virtue in the teachings of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, two of the most prolific scholars on virtue. Most people have heard of Aristotle, the ancient Greek philosopher whose Nicomachean Ethics remains perhaps his best-known work.

Thomas Aquinas, although not as well-known to the casual observer, was no less important. He lived in the mid-13th century when universities emerged as the centers of European discourse. As a professor at the University of Paris, Aquinas maintained an openness to the truth — whatever its source — and actively integrated pagan, Jewish, Muslim, and Christian texts into his writing. In fact, the University of Paris censored him for his extensive reliance on Aristotle’s writings, which had only been rediscovered and translated into Latin in the previous century. Many of Aquinas’ colleagues and superiors perceived Aristotelian cosmology and philosophy as a threat to Christian theology. Aquinas’ interdisciplinary, integrative, and truly global approach to philosophy serves as a compelling example of intellectual curiosity for our contemporary age.

Thought and action are inextricably linked to virtue.

Action theory, the study of how and why we act and make decisions, is another philosophical discipline that developed alongside the study of virtue. Action theory helps us understand our own decision-making processes, which ultimately can make us better military leaders. Aristotle viewed authentic, lasting happiness (eudaemonia in Greek) as the highest good, which we seek out through our acts. In other words, happiness comes from the choices we make in true freedom.

Aquinas’s action theory centers upon his anthropology of the human person. He accepts Boethius’s definition of a human person as an individual substance of a rational nature.[iv] This substance is made alive by his soul, anima in Latin (cf., animated) or psyche in Greek (cf., psychology). Aquinas asserted that the human soul, at its highest level, possesses two rational faculties: the intellect and the will. The intellect drives our search for truth and knowledge, and the will our search for goodness and love. The interaction of our intellect and will informs our choices. For example, within our intellect we can form an intention to go out for ice cream. Once we decide, using our will, to actually go get ice cream, we must then deliberate on the means by which we accomplish this task, i.e. drive, walk, Uber, or order ice cream through Door Dash.

For Aristotle, virtues help us cultivate the skills necessary to arrive at eudaemonia. He defined virtue as the disposition to achieve the mean between two extremes in feeling and in action.[ii] For example, the virtue of fortitude is the mean between cowardice and daring. Put simply, virtue is the practice of excellence. In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle describes virtue as “that which makes its possessor good, and his work good likewise.”[iii] Aristotle and Aquinas both posited that habit forming is achieved through repetition. They contend that true excellence is not “merely” doing something praiseworthy once, but rather performing at that level through habit over time. By habitually practicing virtue, we come closer to being a virtuous person. While we are not born with the cardinal virtues, we can cultivate them through observing virtuous people and repeating the actions we see them perform, adapting them to our own circumstances.

We can compare prudence’s role in virtue to the Army Infantry’s role as queen of battle: the Infantry achieves the decisive point in military operations.

Prudence is the virtue of practical wisdom that links thought to action. It is also “the virtue of choice and decision, of personal responsibility, or risks consciously taken. It belongs to prudence to bring to conclusion the deliberative process, by proposing a course of action in a specific, unique, and unrepeatable situation.”[v] Put succinctly, prudence is “right reason in action.”[vi] Most military leaders are familiar enough with the doctrinal concept of “prudent risk.” But our doctrine falls short in describing prudence more broadly. Prudence is the queen of virtues since it governs all others. We can compare prudence’s role in virtue to the Army Infantry’s role as queen of battle: the Infantry achieves the decisive point in military operations. While other capabilities and war fighting functions shape the operation and help to mass combat power, the battle is won by boots on the ground. Similarly, prudence guides the other virtues to right action. One cannot be truly courageous, just, or temperate if one has not first acted prudently.

Connecting this observation to Aquinas’s anthropology, prudence links how we think (our intellect) with how we act (our will) by perfecting the thinking essential to any choice. In other words, prudence perfects the intellect as preparation for action—we cannot choose well unless we think rightly. This directly applies to how we make decisions, both inside and outside of the military.

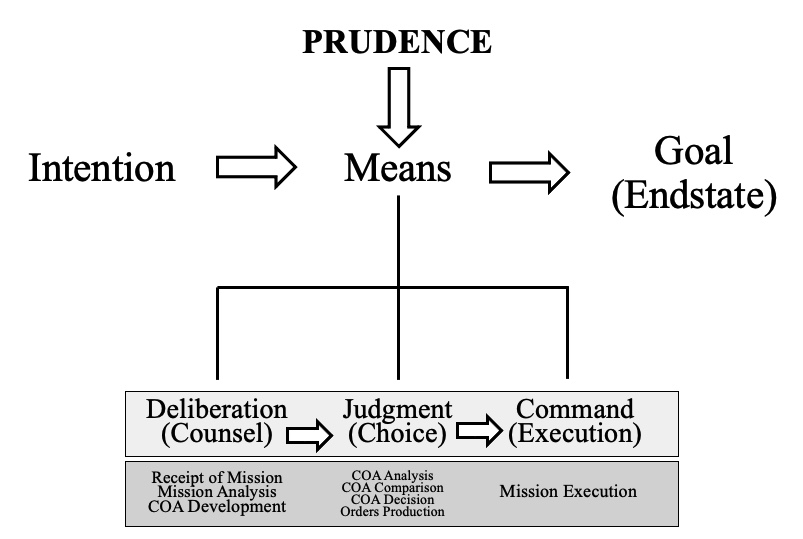

Aquinas teaches that in every act, we first form an intention and a goal. Prudence helps us determine the means by which we move from an intention (thinking) to achieving our goal (action). The prudential means include three steps: (1) deliberation (or counsel); (2) judgment (or choice); and (3) command (or execution).[vii] The first two steps of deliberation and judgement predominantly involve the intellect, but the third step of command builds a bridge towards the will and readies us for choice and action.

During the first step of deliberation, we use our intellect to determine our desired end-state. We are attentive to objective reality and the principles we have learned through personal experience and instruction. Within deliberation, we consult our personal experience and memory while also asking for advice and taking counsel from others. This step requires humility, reflection, and shrewdness. We can act imprudently or indecisively within the step because of several vices. The most common vices are pride, an unwillingness to seek or accept advice, and precipitation, or moving too quickly through the decision-making process. Military leaders routinely practice prudential deliberation within the Military Decision-Making Process’s three initial steps of Receipt of Mission, Mission Analysis, and Course of Action Development. We’ll spare the reader another tutorial on MDMP and instead use an example of individual decision-making to illustrate prudence’s first step in action.

We can think here of a junior Army officer contemplating her next duty assignment. Suppose she is a captain at the engineer career course discerning between three assignments: one tactical, one strategic, and one as an instructor within Training and Doctrine Command. Her goal, or end-state, is to serve as an English professor at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point after completion of her key developmental captain assignment. In this first step of prudence, then, she will seek counsel from her branch manager, mentors, and hiring managers in West Point’s Department of English and Philosophy. She will gather facts about company command opportunities at each assignment, what is required to be a competitive applicant to the Department of English and Philosophy, and the timeline for attending graduate school ahead of teaching at West Point. She will also assess her own knowledge, skills, and behaviors to determine which assignment best suits her strengths and update her Assignment Interactive Module 2.0 resume accordingly. The officer can additionally consider each unit’s mission, upcoming training and deployment schedule, and command climate.

Within the second step of prudence – judgment – we apply a universal principle to the particulars of our situation.

Within the second step of prudence – judgment – we apply a universal principle to the particulars of our situation. This involves sorting through and prioritizing the relevant principles and doctrine. Using foresight, we try to envision the results and examine second and third order effects. We exercise caution and assess risk. Vices within this second step include thoughtlessness and craftiness. Thoughtlessness can occur even if we have deliberated well, and often results from a failure to examine second and third order effects. Craftiness refers to being sly or deceitful, and particularly applies to how we can gloss over or downplay certain risks. If any of this sounds familiar, it’s because military leaders follow these same measures in the fourth through seventh steps of the Military Decision-Making Process: in analyzing, comparing, and deciding upon courses of action, and in Orders Production (see Figure 1, above).

Returning to our example of the engineer captain, in the judgment step she organizes all her gathered information and compares her options. If she feels an intense drive to consider all possible outcomes, she may even wargame her assignment courses of action against one another. Suppose that in the previous step, she learned that she could assume command in the tactical unit within 12-15 months and that the Training and Doctrine Command instructor position would not count as a key developmental assignment. Suppose she also learned the strategic assignment has a long command cue, and the brigade commander has told her she should not expect to take command for at least two years. Moreover, our captain learned that she must start graduate school no later than three years from now to meet the timeline to teach at West Point.

She would deceive herself by thinking that she could simply show up to the strategic unit, out-perform her peers, and immediately move to the front of the command cue. This wouldn’t be impossible, but if she is truly oriented on her goal of teaching at West Point, she should not dismiss this potential risk so easily. After comparing all three courses of action with the information gathered, she decides to pursue the tactical assignment.

The final step, command, most directly involves the will and is the most important step of prudence.

The final step, command, most directly involves the will and is the most important step of prudence. Here, we know what we should do, and we actually do it. As Aquinas wrote, “it matters not only what a man does, but also how he does it; that he do it from right choice and not merely from impulse or passion.”[viii] Admiral William H. McRaven rightly points to the strengthening of the will in getting up each morning to make one’s bed. Having command of the small things increases our command of the larger things, which leads to happiness with the perception of a tidy room and happiness in the long run with more goals achieved.

Our engineer captain, in this final step, would list the tactical assignment as her top choice. She would devote the remainder of her career course time to mastering engineer tactics, Troop Leading Procedures, the Military Decision-Making Process, and physical fitness. It would also be prudent of her to take the Graduate Record Exam during the career course and send her scores to the West Point Department of English and Philosophy. Additionally, she could begin her professor application packet and improve upon it in the years ahead.

The ancient world referred to prudence as the auriga virtutum: the charioteer of the virtues.

Regardless of where you are in your military career, hopefully we have demonstrated that prudence is something we exercise quite often. But practicing prudence, or any other virtue, well is difficult. It requires dedicated repetition and introspection to truly achieve the excellence of which Aristotle wrote. Our decisions are often complicated by additional challenges like time constraints, finances, family, and health, to name a few. But once we actually understand prudence, we can apply it to every aspect of our lives and become better decision-makers.

The military already has institutional mechanisms in place to promote prudence, such as its emphasis on mentorship, After Action Reviews, and codifying lessons learned. But while the military devotes substantial time and energy to teaching decision-making processes, it usually skims over the anthropological and classical foundations of individual decision-making and action theory. The military therefore risks and over reliance on institutional mechanisms and processes to facilitate decision-making, rather than cultivating virtue and character to improve individual powers of judgment. Military leaders who grow in virtue will think rightly and therefore choose well, armed with strong character and a reliable moral compass. Necessary for those other virtues is prudence, which the ancient world referred to as the auriga virtutum: the charioteer of the virtues. Just as the Infantry battle cry exclaims “Follow me!”, prudence leads the way in good action, beckoning all other virtues to follow.

About the Authors:

Mr. James Hickman graduated from West Point in 2006. After serving as an Infantry officer, he completed graduate studies in philosophy and theology at the Catholic University of America and the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas in Rome. He serves the Army in the National Capital Region.

Brigid Calhoun is an active duty Army Military Intelligence officer serving as a Joint Chiefs of Staff Intern at the Pentagon.

The authors are grateful to Matthew Goldammer and Kelly Gallagher for their comments and feedback on this article.

Endnotes:

[i] Paul J. Glenn, “Truth” in A Tour of the Summa Catholic Theology.info, http://www.catholictheology.info/summa-theologica/summa-part1.php?q=34 (Accessed March 31, 2021.)

[ii] “Ancient Ethical Theory,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, February 5, 2021, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-ancient/, (Accessed March 31, 2021.)

[iii] Aristotle as quoted by Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologia (ST) I-II, Q55, A3, SC.

[iv] ST I, Q29, A1, O1 and Teichman, Jenny. “The Definition of Person.” Philosophy 60, no. 232 (1985): 175–85. doi:10.1017/S003181910005107X.

[v] Jean-Pierre Torrell, Aquinas’s Summa: Background, Structure, & Reception (CUA Press), pp. 44-45.

[vi] ST, I-II, Q57, A4, C2.

[vii] For an excellent explanation of the three steps of prudence, see: Aquinas Guilbeau, O.P., “Commanding Prudence,” The Thomistic Institute, podcast audio, October 31, 2020, https://thomisticinstitute.org/podcasts/commanding-prudence-ac2r9?rq=prudence.[viii]ST, I-II, Q57, A4, C2.