The Dostoevsky Lens: What The Brothers Karamazov Teaches Us About Putin & Ukraine

Introduction

Much of the commentary detailing why Russian President Vladimir Putin would want to invade Ukraine points toward the expected geopolitics. His obsession with power. Avenging the fall of the Soviet Union and reclaiming “lost” Russian territories. The economic opportunities Russia could realize through territorial expansion, despite the potential near-term damage Western sanctions could impose. In his own words, Putin believes the Ukrainian people and territory are inherently part of the Russian people and territory. In his mind, he’ll take what is rightfully his.

As an intelligence officer and history nerd, I find it fascinating to study the motivations of our adversaries. These educational endeavors frequently highlight the overwhelmingly human component of warfare and grand strategy. While I would never characterize myself as a Russia or Putin expert, in this article I’d like to offer a lens through which to evaluate why the Russian president has amassed as many as 190,000 troops along the borders of Ukraine. In search of answers over the past month, my mind has routinely returned to Fyodor Dostoevsky’s masterful novel, The Brothers Karamazov. This is not merely because former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger once described Putin as “a character out of Dostoevsky…a man with a great sense of inward connection to Russian history as he sees it.” It’s because Dostoevsky offers profound insight into the centuries-long struggle between conflicting manifestations of the Russian identity. He achieves this by assigning the various identities to five men in the Karamazov family and demonstrating how Western influence and straying from the authentic Russian identity lead to the family’s destruction. For Dostoevsky, the Karamazov family is a microcosm of the Russian nation. To save Russia, its citizens must reject the secular, individualistic revolutionary ideologies of the West and resurrect a Russian identity grounded in common spirituality and connectedness achieved through shared suffering. In short, to be Russian requires orientation towards a transcendent telos (the Greek word for “endstate”), that is not limited to this world.

What does any of this have to do with Putin? Dostoevsky helps us examine the Russia-Ukraine situation beyond geopolitics and look deep into the heart of Russian culture. The novelist enables us to entertain the idea that Putin’s strategic outlook bears eschatological and spiritual qualities similar to his own. While many would not associate today’s Western culture and political thought with the revolutionary ideology of the mid-19th century, Putin likely views both as identical foreign threats from which he must protect Russia. Knowing that he is an astute student of history, we can posit that Putin studies the discipline through a teleological lens. It is not difficult to sense that Putin’s incremental land grabs—Georgia in 2008, Crimea in 2014, and possibly a sizable portion of Ukraine in 2022—point towards a specific telos that he has in mind. Additionally, Putin’s very public displays of piety and support for the Russian Orthodox Church underscore the value he places upon spirituality and culture. Examining Dostoevsky and the Karamazov family in greater detail can help illuminate Putin’s ultimate goal.

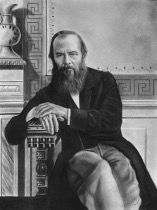

Background: Fyodor Dostoevsky

I read theThe Brothers Karamazov almost exactly one year ago for a graduate course in political theory. My professor, Dr. David Walsh, described it as a “polyphonic novel” in which multiple melodies, characters, and stories intertwine to draw the reader into the perennial Russian identity crisis.

To best understand the book, it is first important to understand Dostoevsky. “Fully part of the disaffected intelligentsia of Russian society,” he got caught up in the revolutionary spirit of Europe in 1848—France, Germany, Austria, Prussia, Hungary, and Italy all experienced socialist or Marxist revolts that year.[1] Dostoevsky wanted Russia be the next country to overthrow its ruling class, but was jailed in 1849 for association with radical communists. He was blindfolded, put in front of a firing squad, shot at with blank rounds in a mock execution, and shipped off to a Siberian work camp for several years.[2]

At the camp, he experienced a profound Christian conversion, leading him to reject Western European ideology. For Dostoevsky, the gradual opening to the West that began in the 18th century under Peter the Great and continued into the 19th century with Marxism would only lead to Russia’s self-destruction. Dostoevsky found Western ideology empty and limited to this world—concluding that it would only lead to a dead end. He further characterized the ideology as inherently individualistic and lacking in solidarity. Rather than destroying and rebuilding society according to ideology, he became convinced that society only changes when individuals are touched by something transcendent. This spiritual orientation would lead individuals, and ultimately society, beyond this world towards redemption.

Unpacking The Brothers Karamazov

Dostoevsky experienced the crisis of Russian identity in a deeply personal way, and in The Brothers Karamazov he pulls his readers into an intimate experience of their own. A separate essay describes the novel as Dostoevsky’s “dystopian warning about what would happen if Russia did not return to its pre-Petrine origins.”

The story opens by introducing the five Karamazov men:

· Fyodor: The wealthy 55-year-old father whose first wife grew to hate him, and left him for another man. Fyodor becomes a womanizer and drunk, prone to dramatic emotional outburst but still able to amass and manage a fortune. He takes far more interest in women than his offspring. Fyodor’s character remains static throughout the novel. He represents the Russian identity of a broken, fatherless family.

· Dmitri: Fyodor’s eldest son and only child from his first marriage. Dmitri shares his father’s volatile temperament and love of women and alcohol. Gambling is another vice that often leads him into trouble. A career military officer, Dmitri reconnects with his father to collect his inheritance ahead of his marriage to Katerina, a local noblewoman. But Dmitri simultaneously lusts after Grushenka, a woman of ill repute who is also romantically involved with Fyodor. Like father, like son. Dmitri represents the militaristic Russian identity.

· Ivan: The 24-year-old middle son and eldest child from Fyodor’s second marriage. Ivan’s temperament is the near opposite of his father’s and older brother’s: he is reserved and unemotional, but intellectually brilliant. Ivan falls in love with Dmitri’s fiance Katerina. Ivan has been studying in a Parisian university and is an ardent atheist. His maxim, “if there is no God, everything is morally permissible,” leads to family tragedy. Ivan represents the post-Enlightenment Russian identity; in embracing the West and rejecting God and Russian culture, he brings destruction upon his family.

· Alyosha: The youngest son, aged 20, and Ivan’s full brother. Both Dostoevsky, in the novel’s preface, and the narrator, in the opening chapter, identify him as the hero of the novel. Alyosha is a novice in the local Russian Orthodox monastery. His deep faith stands in stark contrast to Ivan’s atheism. Alyosha treats everyone with compassion and brings peace to volatile situations, and is loved by all the other characters. Alyosha represents the best of Russia, and Dostoevsky upholds him as the ideal Russian identity.

· Smerdyakov: Although not revealed until later in the novel, Smerdyakov is the bastard son of Fyodor and “Reeking Lizaveta,” a mute homeless woman who died alone giving birth to him. The name “Smerdyakov” means “son of the reeking one.” Fyodor’s servants raised him, but he proved to be a difficult child. After being struck in the face by a servant as a youth, Smerdyakov begins to experience epileptic seizures. Smerdyakov grows up to serve as Fyodor’s cook and lackey, and comes to deeply admire Ivan and adopt his atheism. Because of his epilepsy and servant status, other characters overlook his intelligence. Smerdyakov, like Fyodor and Ivan, represents the brokenness of the Russian family and destruction brought about by an embrace of Western ideology. And, like his father, his character remains static.

Perpetual conflict and tragedy may seem inevitable for the Karamazov family, given the animosity between Fyodor and his sons. But the dialogue between the characters offers numerous opportunities for forgiveness, grace, and reconciliation. Sadly, Fyodor clings to sensual pleasures, Dmitri retains his explosive personality, and Ivan descends deeper into nihilism. The family’s destruction commences with Fyodor’s murder. Each son’s resentment for his father rationally translates into a motive for murdering him. While the narrator does not immediately disclose the culprit, local authorities soon charge Dmitri with murder due to his financial incentive to rob his father to pay off gamling debts and his previous threat to kill Fyodor over Grushenka. Dmitri submits to the trial but is unwilling to accept the punishment, and maintains his innocence.

After Dmitri’s arrest, Ivan meets three times with Smerdyakov to figure out who might have murdered Fyodor. Neither Ivan nor Alyosha were home the night of the murder. Smerdyakov was, but experienced an epileptic seizure at the time of Fyodor’s death. As Ivan tries to solve the murder mystery, he gradually descends into madness and wonders whether he bore any responsibility for his father’s death because of the resentment he bore. During their last meeting, Smerdyakov confesses that he faked his seizure and murdered Fyodor. Horrified, Ivan asks his brother why he would do such a thing. Smerdyakov replies that Ivan gave him the freedom, and is complicit in the murder, by teaching him that anything is morally permissible when there is no God.

That night, Ivan has a nightmare in which he is visited by the devil, who caricatures Ivan’s own beliefs on morality. Alyosha awakens Ivan from this torment, informing him that Smerdyakov hanged himself. Despite his private confession to Ivan, Smerdyakov’s suicide means that he cannot be tried for the murder. Dmitri remains the prime suspect, and his fiance Katerina falsely incriminates him during her court testimony in retribution for Dmitri’s infidelity with Grushenka. He is ultimately found guilty and sentenced to twenty years of hard labor in Siberia.

During the trial, Alyosha circulates amongst Dmitri, Ivan, Smerdyakov, Katerina, and Grushenka, offering them comfort in the midst of their heartbreak and despair. He heals their spiritual wounds and opens doors for forgiveness. In doing so, the other characters atone for their sins and rediscover a semblance of faith. The novel ends with Alyosha and Ivan helping Dmitri and Grushenka escape to America to avoid his court sentence.

Dostoevsky and Russia Today

That the two static characters, Fyodor and Smerdyakov, both die, is not a coincidence. Through their deaths, Dostoevsky alludes to the dead end of the broken Russian family. The characters who develop over the course of the novel – Dmitri, Ivan, Alyosha, Katerina, and Grushenka – are connected through their shared suffering. They become a redeemed family by the story’s end, primarily due to Alyosha’s positive influence on them. Dostoevksy affirms the youngest brother as the hero of the novel.

Whereas Leo Tolstoy wrote about events of the past and a world that was disappearing, Dostoevsky wrote about the future of Russia. Today, 141 years after Dostoevsky’s death, Vladimir Putin finds himself in a position to redeem Russia and save the nation from self-destruction. Three decades have elapsed since the fall of the Soviet Union, which Putin characterizes as “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the past century” and “a real tragedy for the Russian people.” Putin says this not as a former KGB officer or devoted communist, but possibly in the spirit of Alyosha. Using the Dostoevsky lens, Ukraine has become like Ivan: too oriented towards the West and forgetful of its Russian roots.

While Putin’s tactics often resemble the brash and violent actions of Fyodor and Dmitri, the Russian president perhaps views himself in an Alyosha-type role. Just as the youngest Karamazov believed that the existence of suffering did not detract from a transcendent, unifying telos, Putin might believe that the suffering the Russian people experienced under Mongol rule, during World War II, throughout the reign of the Soviet Union, and in our current age connects them to an enduring Russian identity. Putin spoke to Dostoevsky’s theme of connectedness most obviously in the title of his July 2021 essay titled, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians.” That connectedness posits that we are all responsible for, and part of, the moral order of the world. In Putin’s view, Western ideology only brings about destruction; he, and other Russians, are duty-bound to defend the Russian nation from external ideology and NATO expansion. Like Dostoevsky, the Russian president may in fact believe that the way forward is actually the way back–to a purer, more authentic Russia, safe from the destructive influence of the West.

About the Author

Brigid Calhoun is an active duty Army officer currently serving in the Pentagon. She is indebted to Dr. David Walsh and Mr. James Hickman, her fiancé, for their edits to this article, and for their continued guidance of her intellectual formation.

Endnotes

[1] David Walsh, After Ideology: Recovering the Spiritual Foundations of Freedom, (San Francisco: Harper Collins, 1990), 46.

[2] Ibid, p. 46.

References

Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. The Brothers Karamazov. Trans. Constance Garnett. Digireads Publishing, 2019.

Walsh, David. After Ideology: Recovering the Spiritual Foundations of Freedom. San Francisco: Harper Collins, 1990.