Stories of Service: Inspiring the Next Generation

By: Brigid Hickman

In our last Thought to Action article, Bret Wilbanks explored the Army’s recruiting problem, emphasizing the Secretary of the Army’s and Chief of Staff of the Army’s call for Soldiers and veterans to tell their stories to the American people. In explaining why we joined and why we have stayed in uniform, our leaders hope that we can better connect with our fellow citizens so that young Americans, and their parents, might consider military service as a path worth taking. While I do not believe there is anything particularly noteworthy about my own journey into the Army, I would like to share the stories of three American servicemembers whose sacrifices significantly inspired my decision to attend West Point. They are Lance Corporal Lester Weber, Second Lieutenant Emily Perez, and Father (Chaplain) Vincent Capodanno, the “Grunt Padre.”

The primary purpose of sharing these stories with the American public, especially children and teenagers, is not merely to boost Army recruitment numbers. The stories are part of our nation’s history and teach the virtues of fortitude and patriotism. They also inspire us to live up to their example. For a child like me who did not come from a military family or grow up near a military base, tales of those who served were among the few touchpoints I had with the armed forces.

Until college, I lived in Hinsdale, Illinois, a mid-sized town 20 miles west of Chicago. While Hinsdale’s population in the 1990s contained numerous World War II, Korean, and Vietnam War veterans, I don’t recall knowing anyone on active duty. But my brother and I did learn a handful of stories about our grandfathers’ service in WWII. Our paternal grandfather was a captain in the Army Air Corps and a B-29 navigator who flew missions out of Guam over the Pacific. Our maternal grandfather rose to the rank of Colonel in the Army Engineer Corps, helping to rebuild Japan from 1945-1950. Unfortunately, he passed away before my brother and I were born, so we grew up only hearing one grandfather’s first-hand accounts of his military service.

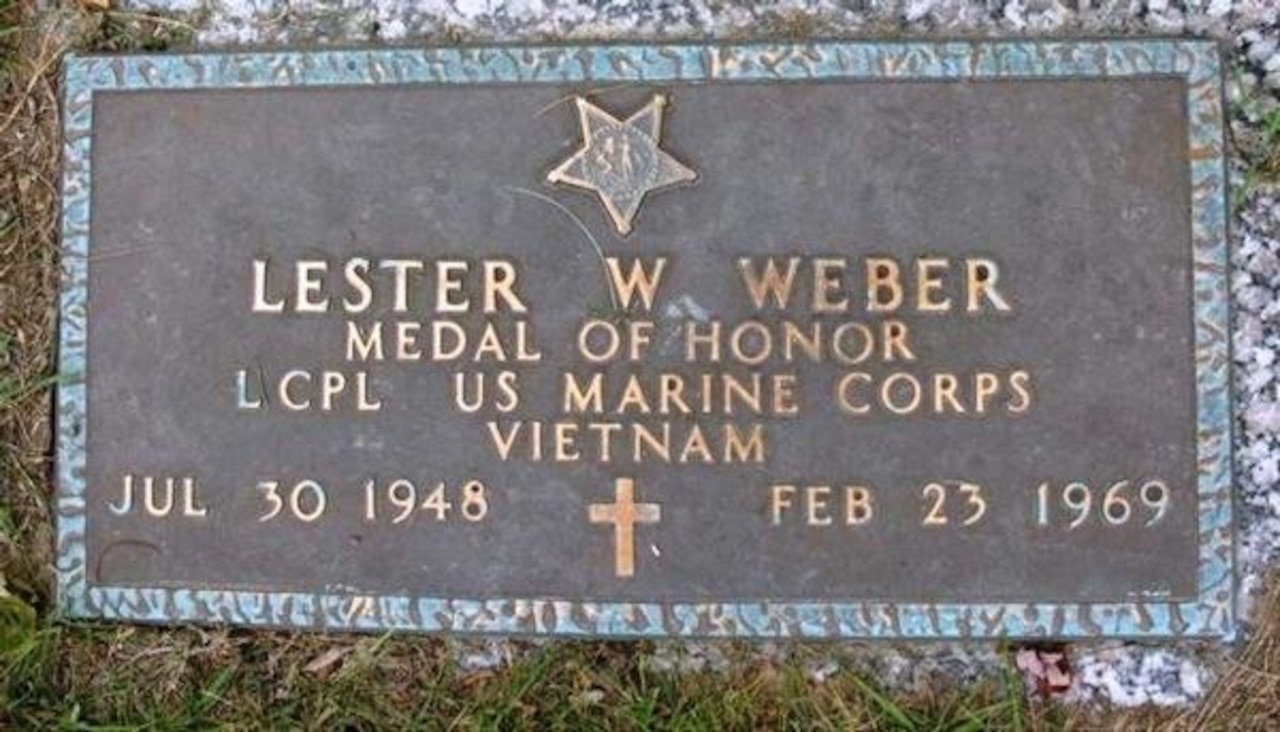

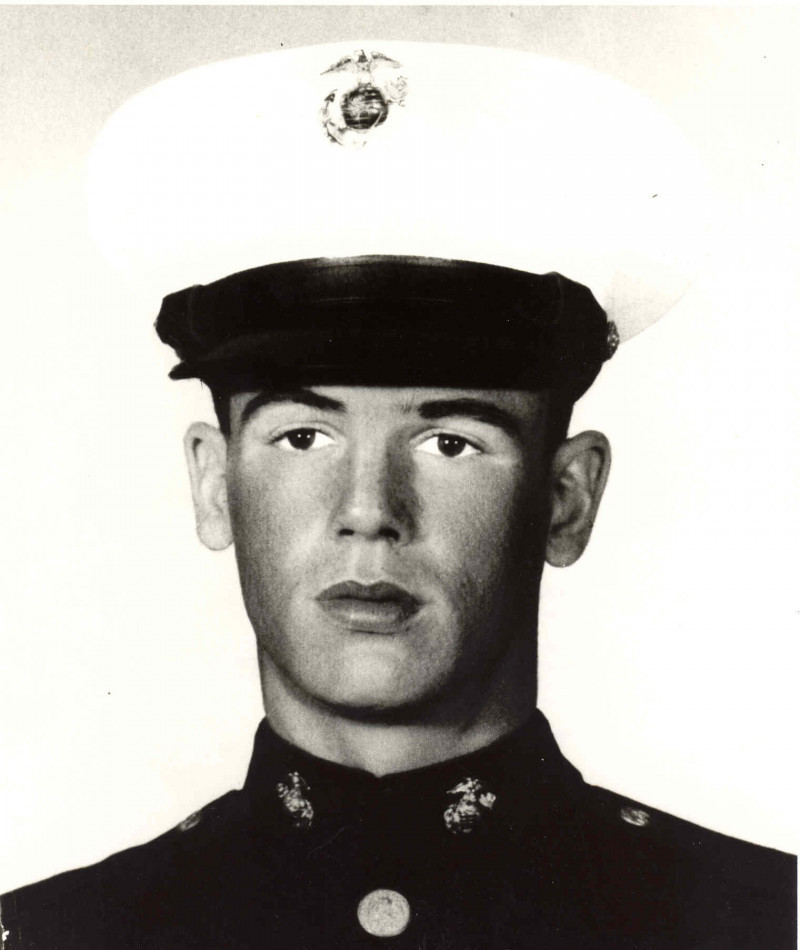

But on Memorial Day in 2003, our grade school erected a monument next to its flagpole in honor of U.S. Marine Lance Corporal (LCpl) Lester Weber, who was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions in Vietnam. LCpl Weber attended our grade school as a child and enlisted in the Marines at age 18. He served an extended tour in Vietnam as an ammunition carrier and squad leader in 7th Marines, 1st Marine Division. On February 23, 1969, while leading his platoon’s search and clear operation, he was attacked by a heavily-armed North Vietnamese Army battalion. Despite being mortally wounded, he attempted to save the lives of two fellow Marines from enemy fire after having overwhelmed four enemy soldiers in hand-to-hand combat. LCpl Weber was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor by President Richard Nixon during a White House ceremony on February 16, 1971.[1]

Our Lieutenant Governor, who had been a grade school classmate of LCpl Weber, presided over the ceremony. Only two dozen or so people attended, but thankfully my dad felt it was important for our family to be there. I had learned about the Vietnam War in my history classes, but the monument’s installation established a personal connection between me and LCpl Weber.

A few years later, on a family trip to Washington, D.C., I found his name on the Vietnam Memorial Wall. A kid from Hinsdale, only six years older than me when he joined the Marines, was enshrined alongside 58,317 other men and women who died for our nation during that war. Visiting the National Mall left the impression that it was important for “us the living” to not only remember “these honored dead,” but to study and learn from the decisions made before, during, and after war.[2]

Fast forward to high school. The attacks of 9/11 and constant media coverage of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq put service to the nation at the forefront of my mind. My parents and a special handful of teachers had inspired my sense of duty and patriotism. Originally wanting to join the CIA, I shifted gears towards West Point after a family friend applied. I submitted my own application my senior year. A month later, I learned of the death of the first female West Point graduate in the Global War on Terror, Second Lieutenant Emily Perez. She died in Iraq on September 12, 2006 when an improvised explosive device exploded under her vehicle. She was buried in the West Point cemetery on Tuesday, September 26, 2006.[3]

Two days later, on Thursday, September 28, I visited West Point for the first time. I attended classes with a female plebe and spent the night in her barracks room. My parents and I fell in love with the beautiful campus and the academy’s rich history and tradition. We were inspired by everyone we met, and I felt like I had found where I was meant to be. Towards the end of our visit, we walked through the cemetery and stopped at Emily’s grave. It was a mound of fresh dirt. The reality hit that attending West Point and commissioning into the Army came with serious risk, regardless of your branch or sex. Emily’s life, cut short by war, gave us pause to weigh the decision before us as a family.

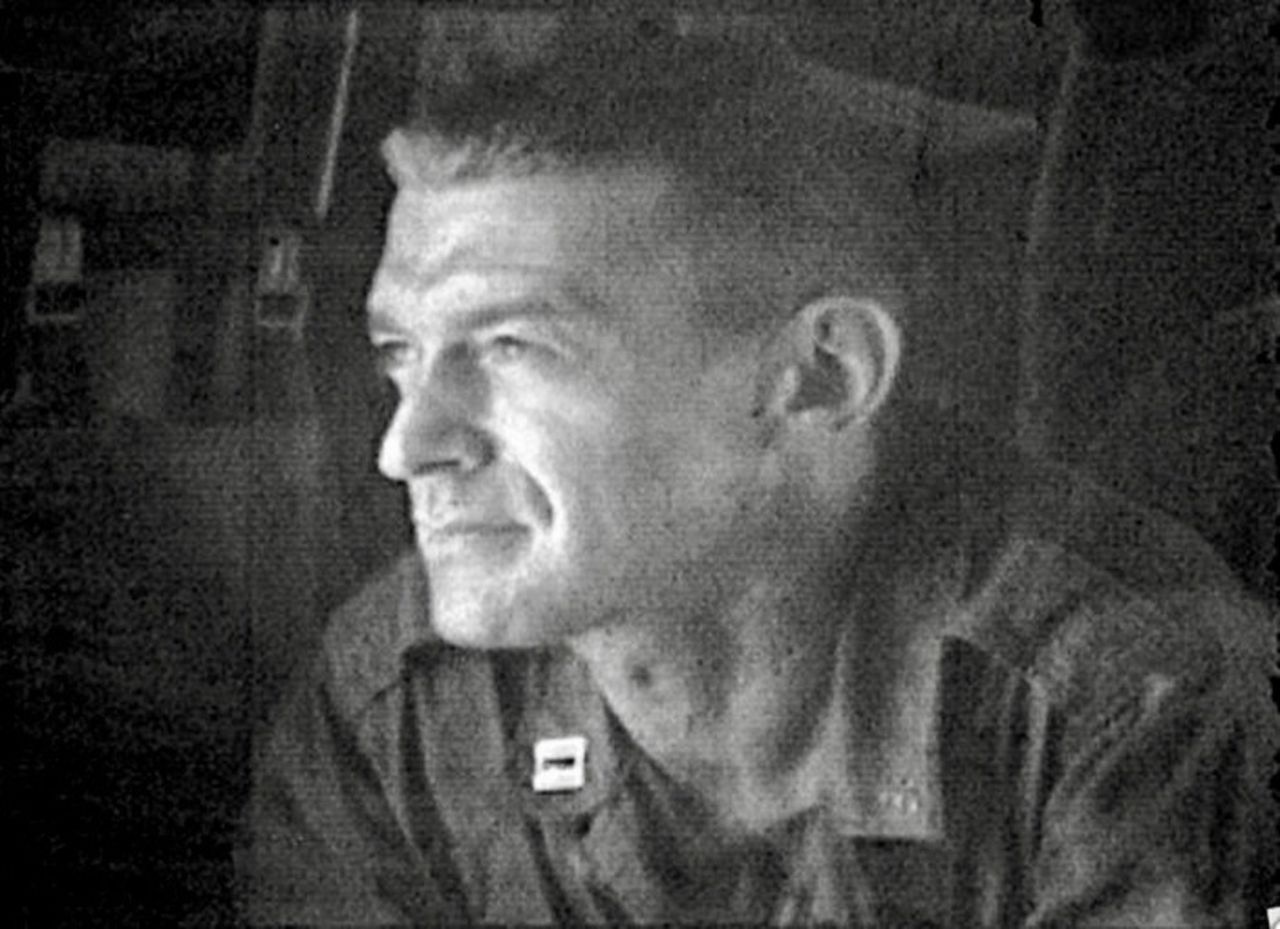

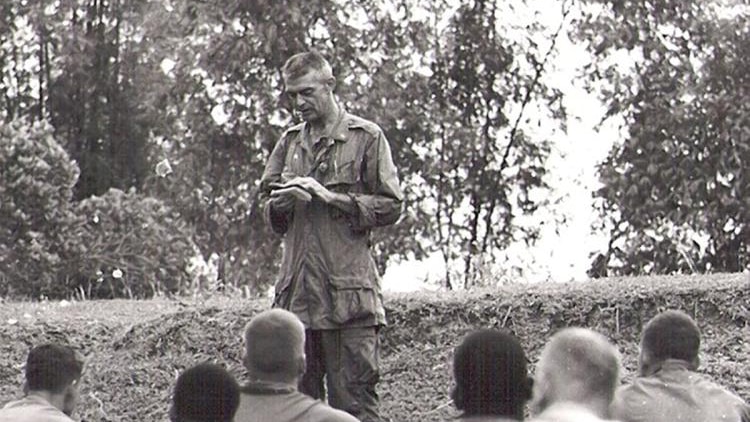

The final story to share here is compelling not only because of its heroism, but also because the protagonist gave the ultimate sacrifice exactly 55 years ago this weekend. At some point during grade school, I first learned about another Marine Medal of Honor recipient: Father Vincent Capodanno. A Catholic priest who served as a chaplain during the Vietnam War, his Marines affectionately nicknamed him the “Grunt Padre” because he lived, slept, ate, and patrolled with the troops, just as a shepherd does with his sheep. Like LCpl Weber, Father Capodanno extended his tour beyond the 12-month requirement to remain with his battalion.

Marines and South Vietnamese villagers grew to love the Grunt Padre who always made time to administer the sacraments, console them, and build libraries and chapels for them. On September 4, 1967, Father Capodanno made the ultimate sacrifice when his battalion of 500 Marines were ambushed by approximately 2,500 North Vietnamese soldiers. The words of Marine Corps Dr. Joseph E. Pilon, in a letter to a group of nuns in January 1969, beautifully describe the Grunt Padre’s last acts on earth:

“Over here there is a written policy that if you get three Purple Hearts you go home within 48 hours. On Labor Day our battalion ran into a world of trouble. When Fr. C. arrived on the scene it was 500 marines against 2500 N. Vietnamese. We were constantly on the verge of being overrun and the Marines on several occasions had to ‘advance in a retrograde movement’. This left the dead and wounded outside the perimeter as they slowly withdrew. Early in the day he was shot in the right hand – one corpsman patched him up and tried to evacuate him to the rear but Fr. C. declined, saying he had work to do. A few hours later a mortar shell landed near him and left his right arm hanging in shreds. Once again he was patched up and again he refused evacuation. There he was, moving slowly from wounded to dead to wounded, using his left arm to support his right as he gave absolution [also known as “last rites” or “anointing of the sick”], when he suddenly spied a corpsman get knocked down by a burst from an automatic weapon. The man was shot in the leg and couldn’t move. Fr. C. ran out to him and positioned himself between the injured boy and the weapon. The weapon opened up again and this time riddled Fr. C. completely, and – with his third Purple Heart of the day – Father went Home. And that, Sisters, is my Christmas message to you – the one conveyed to me by Father Capodanno, the message of love.”[4]

Father Capodanno was shot 27 times by the enemy machine gun. That was a powerful image for me to comprehend as a grade school student, much like Emily Perez’s dirt grave was as a high school senior. The lives and deaths of LCpl Weber, 1LT Perez, and Chaplain Capodanno represent the best of a nation that is not perfect, but is always striving to become “a more perfect Union.” We can debate and disagree with the causes of the wars in which they fought and died, but our time is better spent in reflection and gratitude for their willingness to raise their right hands and lead in combat.

We need more good men and women willing to take the same oath. Ours is a nation worth defending, just as LCpl Weber, 1LT Perez, and Father Capodanno believed.

[1] Lange, Katie. “Medal of Honor Monday: Marine Corps Lance Cpl. Lester Weber.” Department of Defense News, February 21, 2021. https://www.defense.gov/News/Feature-Stories/story/article/2506378/medal-of-honor-monday-marine-corps-lance-cpl-lester-weber/

[2] Lincoln, Abraham. “Gettysburg Address.” Delivered at Gettysburg, PA on November 19, 1863. Accessed via The Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbpe.24404500/?st=text

[3] “61938 2LT PEREZ Emily Jazmin Tatum USA.” https://www.west-point.org/users/usma2005/61938/

[4] “Father Vincent R. Capodanno.” Maryknoll Mission Archives. https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-fathers-bro/father-vincent-r-capodanno-mm/