So You Wanna Be a Speechwriter: Three Tips To Get You Started

Hook and Intro

On the family tree of writing, you can find one off-kilter cousin dangling from a distant branch. Closer to the center of this genealogical analogy are prose, poetry, and all of their children from memoir to short story. Sure, there are other funky distant relatives as well like copyediting and ghostwriting, but the former is always going to correct you and the latter you can’t find. But you’ll know speechwriting when you see her. Your twice-removed cousin sits alone at the family reunion drinking in every detail of the festivities and an overpriced IPA. If you’re thinking about leaving the stable and sturdy trunk of traditional writing and exploring the less-traveled branch of speechwriting, Here are three tips to get you started:

Three Words: Principal, Principal, Principal

Speechwriting is not about you or what you want to say. At all. Not even a little bit. It’s about what your principal — the person for whom you are writing — wants to say. The art of speechwriting starts with the acknowledgment that your task is to carefully, thoughtfully construct a speech you will never deliver. The principal will be held accountable — positively and negatively — for the words they commit to the arena of public opinion. It’s important to remember that the main reason they are not personally writing their own speech is because they lack the time to do the line-by-line work, especially against a whole portfolio of competing, urgent, and important priorities. The principal needs a person to bring their ideas and messages into cogent, compelling form. They need someone to package rigorous research into relatable messages — that’s the speechwriter.

Edits Equal Engagement

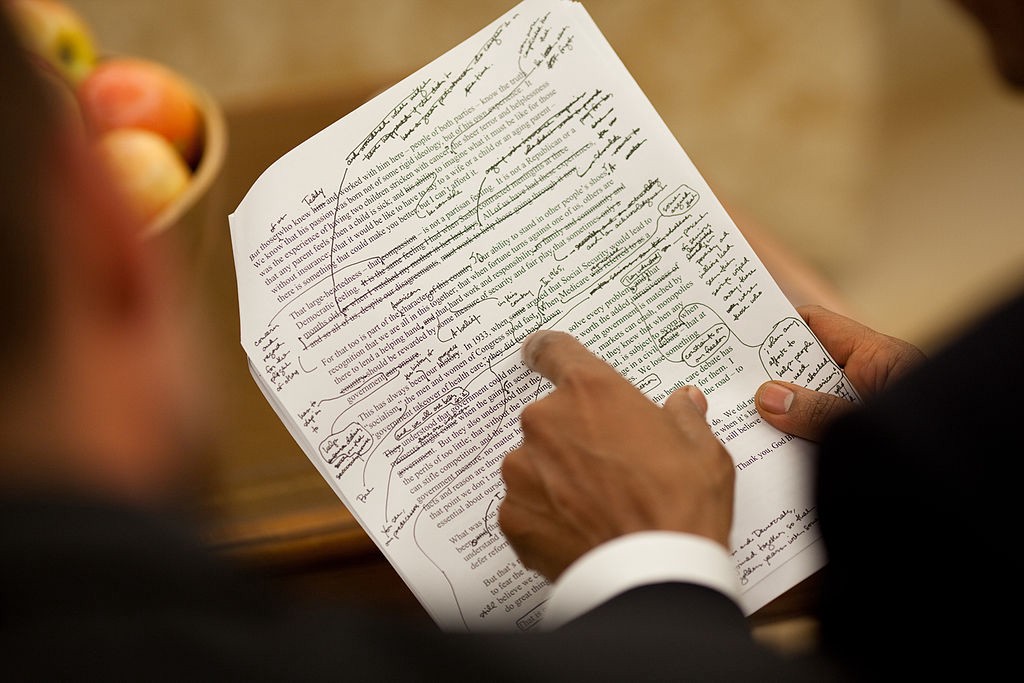

If you’re thinking of going into speechwriting, do yourself a favor and disabuse yourself of the notion that one bright, sunny day you’ll submit a draft to your principal and it will come back to you without a single edit. The eggshell sheets, gingerly thumbed through, will levitate into your hands glowing with the approval of full, unadulterated agreement and you and your principal will have achieved a symbiotic nirvana. This is a fantasy and a deluded nightmare in disguise. Edits are good. In fact, they’re great. Edits are evidence of progress towards the principal’s desired state. They are physical proof that your principal is interacting with your writing and engaging by adjusting the azimuth here and there.

Yes, it can be a little unnerving to see your tidy pages of black and white come back with what appears to be hieroglyphics scribbled in blood, but consider the implications of the elusive zero-edits situation. What does that really mean? It means a) your principal didn’t read it b) thought it was so bad they couldn’t engage with it, or c) doesn’t care enough about the event to dedicate any time to enhancing the speech whether they thought it was good or bad. I’ll take the edits please.

Part Writer, Part Wedding Planner

Stop watching the West Wing. Or better yet, to calibrate expectations, revisit 2001’s The Wedding Planner featuring Jennifer Lopez and Matthew McConaughey and find a way to make your peace between the Sorkin masterpiece and this movie because together they form a more accurate representation of speechwriting. And the reason is, as I’m sure wedding planners endlessly exhort, details make or break the day.

- Who will speak before your principal? What are they going to say? Will they cite facts and figures that could conflict with your principal’s? Whose numbers are accurate and does it matter? Who will speak after?

- Is this an outdoors event? What’s the forecasted weather if so? Clear skies and blearing sun can actually be bad because if you’re using page protectors, the sun can bounce off the clear plastic and create a distracting (if not blinding) glare.

- How tall is the podium? What is it made of? Is it adjustable and at what angle will the speech rest with respect to the principal? Is there a detachable mic? Is teleprompter an option? Who will control the speed of the teleprompter feed?

- Who else is going to be there? Is there a reception and green room walk-through before the speech? Who will brief the principal? Are there relationships you can leverage in the speech to build quick rapport with the audience?

These are just some of the questions that will begin to inundate your brain well before you think of your hook, intro, three substantive points and closer. The more time you invest in understanding the finer details of the holistic event, the more you will be able to envision how it will unfold in reality and strike the tone that will add to the harmony of the event. The last thing you want to do is send your principal up to the podium with a great speech that goes poorly because of a mechanical detail (i.e. using a binder cover that looks like another speaker’s, forcing your principal to search for their remarks as everyone uncomfortably watches) or an overlooked social element (thanking an acrimoniously divorced couple in the same sentence). These small missteps can strike notes of anxiety and discord within the atmosphere.

A Bonus Tip: Thoughts on “Know Your Audience”

Because every other speechwriter from the great Peggy Noonan (Reagan’s speechwriter who penned his famous “Boys of Pointe du Hoc” speech for the 40th anniversary of D-Day) to the formidable Teddy Sorenson (JFK’s speechwriter who he often referred to as his “intellectual blood blank”) has passionately enjoined every would-be speechwriter to know their audience, we will quickly gloss over this cardinal rule.

Consider it your penultimate responsibility to place your speech in an environment where your principal can be successful. So in addition to writer and wedding planner, don your yellow raincoat, grab your magnifying glass, and get out there with your best Harriet the Spy. Frankly, it is not enough to just “know your audience.” You have to study the audience from the rank-and-file attendee to the illustrious VIPs. Do the extra research. Employ all your resources to build your principal the very best speech you can produce. Verify facts with historians, find compelling stories tucked away in archives or museums, and reach out to friends and family if an individual is the focal point of a speech. Speechwriting, distilled to its essence, is about connecting with people. So, start with people.

Finally, place yourself in the shoes and headspace of the audience members. Who has their ears pricked for a shout-out and will that be appropriate and/or beneficial for your principal to do that? How long have they already been sitting and listening? Is your principal’s speech the only event separating them from eating dinner, going home, or graduating? How do the remarks you’ve provided your principal stand up against the rest if there are multiple speakers? Is redundancy a potential problem? And of course, invoking tip #1, how can you make your principal’s remarks the best.

Closer

So, there you have it, tips from the trenches. And because I’ve showed no restraint whatsoever in creating mediocre analogies throughout this piece, why stop now? Because the keynote speech is often the meatiest part of an event, you might liken it to the main course of a dinner. Steak probably comes to mind, but think of it more like a fish. Steak is a little too divisive —vegetarians and vegans cannot partake. Fish, however, is more versatile and can capture a broader audience. Some people love it, some people hate it, others are just ok with it, and you might even have vegans making a pescatarian exception for the night. While fish is a versatile main dish and can pair well with many sides, it is prone to absorb accompanying flavors, and if those flavors clash, it will be obvious and unpleasant. And if you’re still reading and speechwriting is something you think you might want to do, a fundamental point to consider if you genuinely enjoy the process of research and writing in an applied setting contoured to the personality, priorities, and position of a principal. More simply, ask yourself the obvious question: do you like fish?

Major Jenn Walters graduated from the United States Air Force Academy in 2011. After serving as a KC-10A instructor pilot, she completed her PhD in public policy at the Pardee RAND Graduate School in Santa Monica, CA. She is currently a speechwriter serving on the Joint Staff, Pentagon, VA.

* The opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not represent those of the U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any part of the U.S. government.