“Simply the Designated Leader:” A Tribute to COL Roger Donlon

By Brigid C. Hickman

“We even boast of our afflictions, because affliction produces endurance, and endurance proven character, and proven character, hope. And hope does not disappoint.”

St. Paul’s Letter to the Romans, Chapter 5, Verses 3-5

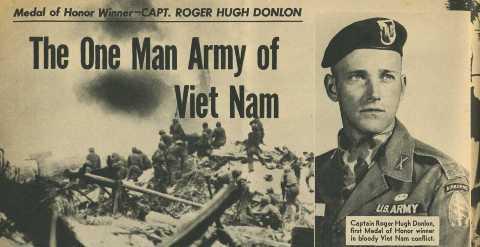

On Thursday, January 25, Colonel (COL) (Retired) Roger H.C. Donlon, the recipient of the first Congressional Medal of Honor awarded during the Vietnam War, entered eternal life after a 12-year battle with Parkinson’s disease. He died five days shy of his 90th birthday.

While I never met COL Donlon, I have known him as 7th Special Forces Group’s preeminent archetype since I arrived at the unit in August 2023. Photos and posters of him adorn the hallways of our headquarters building. A life-sized bust of a young Captain (CPT) Donlon, wearing his Green Beret and Medal of Honor, greets every passerby in the front lobby. My group commander describes him as “one of the giants on whose shoulders we stand.” Admittedly, I did not know much about COL Donlon beyond his Medal of Honor citation. As I read more about his life since Thursday, and after hearing him in his own words, it is clear he was a man of deep faith, magnanimous character, and infused virtue. This article is a meager attempt to draw out COL Donlon’s defining qualities and commend him to our readers as a north star on which to orient the Army officer ethic.

COL Donlon in the lobby of 7th Special Forces Group’s Headquarters building, December 5, 2018. (Stars & Stripes)

COL Donlon’s Early Years

According to his obituary, Roger Hugh Charles Donlon was born in Saugerties, New York in 1934, the eighth of ten children. Donlon described his childhood as full of “tough times” during the Great Depression, but his father, a World War I veteran, inculcated into his children a commitment to hard work and service to others. In a living history video for the Congressional Medal of Honor Society, Donlon credited his mother with “instilling a spiritual dimension” in her children. The seeds of faith she planted in her eighth child would eventually undergird his interior life and public acts of fortitude and charity.

After graduating high school in 1953, Donlon followed his older brothers into the military and enlisted in the U.S. Air Force as an aspiring pilot. “When that didn’t work out,” Donlon recalled in the living history video, “I figured if I can’t fly planes, I’ll try jumping out of them.” His circuitous path to the Special Forces took him back home to the Hudson Valley, where he attended West Point for two years before commissioning as an Infantry Officer through Officer Candidate School. He earned his Green Beret in 1953 and deployed to Vietnam the following year as the commander of Detachment Alpha (Team-A) 726.[1] Camp Nam Dong, a small patrol base in the South Vietnamese mountains 24km from the Laos border, would be Team A-726’s first assignment.

“The Death Pit”

“The Death Pit,” preliminary drawing for “The Battle of Nam Dong,” by Larry Selman

At Nam Dong, Donlon and Team A-726 trained and partnered with Australian Soldiers, 300 South Vietnamese Soldiers and 60 Nung (ethnic Chinese) fighters. Shortly after midnight on July 6, 1964, thirty-year old CPT Donlon neared the end of his guard shift. He had a premonition of an attack, writing to his wife hours earlier: “All hell is going to break loose here before the night is over.[2] In the preceding days, patrols reported skittish villagers outside the camp. On the morning of July 5, another patrol found the slain bodies of two village chiefs who had been cooperating with the Americans. Donlon ordered his team and Vietnamese partners to increase security.

At 2:26AM, CPT Donlon completed his shift and returned to the mess hall to consult the guard roster. An explosion threw him to the ground. Another mortar round directly hit the camp’s command post. Soon more enemy mortar rounds rained down upon the camp, joined by grenades, small arms, and machine gun fire. Donlon and his team sergeant, “Pop” Alamo, tried to put out the flames and maneuver to one of their mortar pits to return fire on their attackers. A second mortar round knocked Donlon off his feet, and out of one of his boots. He managed to crawl into the mortar pit and found his teammate Sergeant John Houston, who informed Donlon of the enemy’s main attack positions outside the camp’s gates. A third mortar round then struck, killing Houston. Donlon received shrapnel wounds to his left arm and stomach; the explosion also knocked off his other boot and most of his equipment except for his rifle and two magazines.[3]

In the ensuing hours Donlon continued moving around the base, coordinating its defense, and shuttling supplies and ammunition between firing positions. He provided covering fire to medically evacuate wounded men from a decimated mortar position. While dragging his severely wounded team sergeant from the same position, Donlon took his fourth direct motor hit. This round killed “Pop” and wounded Donlon’s shoulder. Disregarding his own injuries, Donlon next moved to four wounded Nungs and used his sock and strips of his own shirt as tourniquets for their wounds. Almost every other movement he conducted that night resulted in another injury to a new part of his body, but that did not stop Donlon from fighting, encouraging, and leading his team.

Five hours later, when daylight broke and the attack subsided, Donlon counted the casualties: two Green Berets killed, one Australian Soldier killed, 55 South Vietnamese and Nung killed, and 65 total wounded. He later learned that approximately 100 of the 300 South Vietnamese Soldiers he had been training were co-opted by the Viet Cong and participated in the attack against the camp. This explained the direct hits on the command post and mortar pits. Despite the betrayal of his partner force, Donlon had led the remaining 260 South Vietnamese, Nung, Australians, and Green Berets against a 900-man Viet Cong battalion reinforced with North Vietnamese soldiers. According to Donlon’s obituary, “it was the first battle of the Vietnam War where the Regular North Vietnamese Army joined forces with the Viet Cong from the south to try to overrun an American Outpost.” [3] This type of green-on-blue attack against a remote outpost would sadly repeat itself not only during the Vietnam War, but also during America’s war in Afghanistan decades later.

From Battle to Virtue: “Courage Take from the Green Berets”

On December 5, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson presented Donlon with the Congressional Medal of Honor. “Pop” and Houston each received posthumous Distinguished Service Crosses. All surviving members of Team A-726 received Silver Stars or Bronze Stars with valor devices and joined Donlon at the White House for his ceremony. [4] Introducing them to their commander in chief, Donlon humbly said, “the medal belongs to them, too.” He wrote later that evening, “it was a team effort, and I was simply the designated leader.” [5] Undoubtedly, with these comments we can count Donlon among “men who mean just what they say,” as the Ballad of the Green Beret succinctly elucidates.

Despite his bona fides as a tenacious warrior, Donlon cultivated a well-ordered interior life centered on his faith. A rich interior life includes a strong sense of worth and respect, both for oneself and others. It embodies a commitment to the values of faith, trust, and hope in something bigger than oneself, often resulting in high levels of resilience. In a May 2022 video for the Knights of Columbus, an elderly and gaunt Donlon rolled the red, white, and blue beads of a rosary through his fingers. In measured speech he stated, “these days I spend most of my time praying and counting my blessings. Anybody who has strong faith, it gives you perseverance, a belief in forgiveness, and trust.” For Donlon, that trust was related to his sense of purpose on this earth: “You have God-given gifts, you search and find out what they are.”

Beyond his battlefield courage, Donlon’s gifts clearly resided in his infused virtues of perseverance, humility, and charity. In his Medal of Honor Society living history video, Donlon stated Houston’s death inspired “a need for me to dig deeper.” Just days before the attack, Houston had shared with Donlon a letter from his wife Alice: she was pregnant with twins. Grieved that his young sergeant’s children would never meet their father, he rallied the rest of his team: “we agreed amongst ourselves that we would never surrender, we would die…that was one of the combat multipliers that kept us going.” Donlon’s characteristic perseverance during the battle echoed the resolve he demonstrated in the ten years between joining the Air Force and landing in Vietnam as a Green Beret. Despite the twists and turns in his military accessions journey, he endured and exuded his father’s work ethic.

On charity, Donlon professed: “it’s a great comfort to be a member of the National Medal of Honor Society…a band of brothers amongst whom you never hear the word ‘hate.’ You killed the enemy because of the love you have for the man next to you. The smaller your team, the deeper that love because you know his whole family…so the most powerful emotion on earth is love. We have to time and time again convey that to the next generation.”

Donlon’s commitment to love and forgiveness are perhaps best manifested in his work to convert the Nam Dong battlefield into a children’s library and learning center. He helped dedicate the facilities in honor of the deceased American and Australian Soldiers who died on July 6, 1964. A staunch advocate of education, he hoped the library would help students learn to not repeat the mistakes of the past. [6]

Donlon’s Legacy and Call to Action

Roger Donlon leaves a multi-faceted legacy that impacts beyond the Army Special Forces Community. Arguably, his life after retiring from the Army in 1988 speaks more to his character than his 32 years in uniform: he used his God-given gifts to reconcile with his former enemies, to raise a family in his faith, and to serve as a model of virtue for generations of American civilians and service members.

Having stood thirty feet from Sal Giunta when he spontaneously donated his original Medal of Honor to the 173rd Infantry Brigade Combat Team (Airborne) in July 2017, I am blessed to now serve in another storied organization whose titular veterans have bequeathed cherished artifacts to the unit’s posterity. Very few will be called to demonstrate the extraordinary fortitude that Donlon and Giunta did on the battlefields of Vietnam and Afghanistan, but we can model their humility, charity, and perseverance.

COL Donlon perhaps said it best in an interview with the American Legion: “I tell kids, keep God in your heart, obey your mother and father, and don’t be afraid to do an unsolicited act of kindness.” Our charge is to carry forward his thoughts into our own actions. May his soul, and the souls of all the faithful departed, rest in peace.

CPT Donlon in Vietnam (Stars & Stripes)

By Line for Author:

MAJ Brigid Hickman is an Army intelligence officer assigned to 7th Special Forces Group (Airborne) at Camp “Bull” Simon, Florida.

Opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not represent those of the United States Army, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

[1] https://www.ausa.org/news/vietnam-war-hero-green-beret-legend-dies

[2] https://homeofheroes.com/heroes-stories/vietnam-war/roger-donlon/

[3] https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/kansascity/name/roger-donlon-obituary?id=54214979

[4] https://www.ausa.org/news/vietnam-war-hero-green-beret-legend-dies

[5] https://homeofheroes.com/heroes-stories/vietnam-war/roger-donlon/

[6] https://www.recordonline.com/story/news/2012/05/28/former-enemies-learn-they-have/49619810007/