Over the Prefrontal Cortex Hill? Lessons about Change I Learned from Moving to France

Too Old to Change?

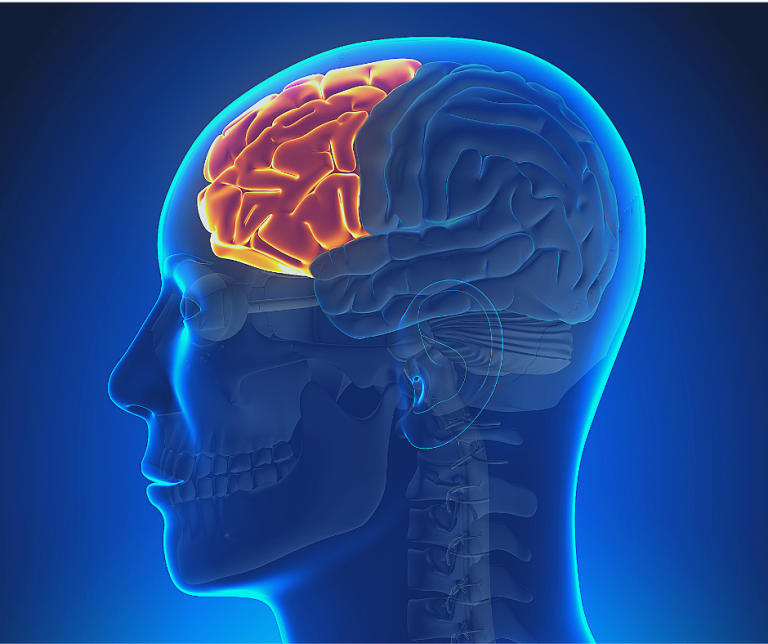

I read once, years ago, that we can expect our prefrontal cortex – the area of our brain largely responsible for thoughts, actions and decision-making – to be fully set at age 25. I always interpreted this with a bit of melancholy rather than relief. At 25 years old and beyond I could anticipate, generally speaking, to make wiser and more responsible decisions. What’s not to like about that? This neurological milestone felt like an expectation wrapped in a warning – you’re an adult now, you should behave in predictable patterns and use your age-based experience to avoid activities that are risky, uncomfortable and unknown. I appreciate the notion that this developmental maturation in our brains helps us assess risk in a more meaningful and comprehensive way, protecting us from danger and recklessness. But the very idea of the brain being set made me uneasy.

Chasing Change

When we think of a person who is set, it often conjures thoughts of stubbornness, strict adherence to certain approaches to accomplishing tasks, intransigent preferences and perhaps an avoidance of things and experiences outside his or her comfort zone. We even have a phrase for this way of life – to be set in your ways. Around the exact same time I learned this ominous piece of brain trivia, I began a personal journey that led me to become deeply focused on a goal – to live abroad. As a cadet at the United States Air Force Academy, I had learned about a program called the Olmsted Scholarship when I was just 18 years old. In a nutshell, the program offered a unique model: separate military officers from their day-to-day operational work and expertise and transplant them into the unknown and unfamiliar through total immersion in a foreign country. It sounded like an experience that would entirely displace and disorient you, a change so complete it would sever set ways and discard familiar dynamics. I wanted nothing more.

Almost a decade later, when I was 33, I was selected for the Olmsted Scholars Program in my very last year of eligibility after many failed attempts. Standing in an alcove of the Pentagon that managed to block almost all cell service, I strained to hear the voice on the other end of a call that would dramatically change my life: “I’m so pleased to inform you….that you’ll be serving your tour as an Olmsted Scholar….in Aix-en-Provence, France.” France. An ocean away, a world apart, and a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see life through an entirely different perspective; this was my chance to unset my ways.

From Zero to French

At the time I spoke no French (and it still feels that way sometimes today). From the outset, the language seemed so nuanced and precise, so easily distorted into oblivion if the pronunciation wasn’t just right and even if it was, the French would know you were an outsider. Even before departing for the country, I cringed with sympathetic embarrassment when I heard customers at our local French-owned bakery ask for a “kwah-san” as they pointed to the display case of croissants. The patrons threw each other quick glances of side-eye. Soon, this would become my whole life.

At the time of writing this, I’ve been living in the historic quarter of Aix-en-Provence for five months, stumbling through political science classes (taught in French) at Science Po, not having a clue where to move or put my hands as a member of the university women’s handball team and generally revealing to everyone I encounter within moments that I am an American through the thickness of my accent. But this experience has obliterated my comfort zone and proved to me that it is still very possible to change how you think and approach decisions beyond the midpoint of your twenties. So whether you are in the before or after of your prefrontal cortex milestone, here are three insights from my language learning experience you can apply anywhere as you seek to escape your own comfort zone:

Growth is Not Linear

For anyone seeking to learn a new language or revisit their studies from the past, I think it is helpful to keep this mantra in your mind – “learning a language is not linear.” However, this applies just as well to any new skill. I’ve heard people talk about epiphany moments or when it “just clicks” and they suddenly become far more conversant and fluent in a foreign language, but I think this is all over-exaggeration or potentially overconfidence. Learning a language is an uneven stepladder of small triumphs and embarrassing failures that amount, surely but slowly, into a heightened capacity to communicate.

The modalities of communication themselves – writing, speaking, reading, listening and even gestural – are all so different and every person will have a distinct experience with building each one. When you find something that works for you (for me, it’s reading newspapers and simple prose books), use that to your advantage and build your vocabulary through the modality that gives you the most enjoyment. Of course, it’s important to balance your learning with your weaker modalities, but we tend to be more consistent with things we enjoy.

Identifying the Difference Between Pain and Discomfort

Much like physical fitness, learning to identify the difference between pain and discomfort in language learning has become critical for me. For example, if you feel pain in your foot but you decide to run through the pain, it often results in worse outcomes in the long-run that require extensive rehabilitation to get you back to baseline. Or, if you set the treadmill at the top speed, you might be able to keep pace but not for long. Similarly, in an effort to be as immersive as possible (or acquire a new skill as quickly as possible), you might decide to overload yourself.

For me, this looked like setting up unrealistic rules for myself: only watch TV in French, read only French texts, take one-hundred percent of my classes in French. This is not sustainable, and like physical fitness, will result in avoidable injury. Your brain can slip into a state called cognitive overload whereby its function decreases appreciably because the demands placed on working memory exceeds capacity. Your ability to retain and recall new vocabulary drops precipitously in this state, but what is most concerning is that it can wound your confidence and motivation. Therefore, be mindful of where your effort level is and willing to dial back when you sense that it is approaching all. Chances are, if you stay there too long, you’ll end up back at nothing.

Saying Yes Sparingly

In recent years, I’ve observed a growing fascination with the concept of “saying yes to everything.” The rationale here is that the more you respond in the affirmative to opportunities that life naturally presents, you will maximize your gain – you’ll learn something new, expand your horizons, and at very worst discover something you don’t prefer but you can say you’ve tried it. In theory, I appreciate that this idea harnesses the power of optimism and broadmindedness, but its weakness lies in the inevitable expenditure of time and realities of prioritization. When I arrived in Aix, there were so many ways I could choose to spend my limited time here, especially through my association with the university. I signed up for a wine club, historical society, joined a CrossFit gym (and another gym), tried out for rugby and handball teams, and somehow due to a language barrier became briefly involved with a Polish heritage group. Paired with a full course load in French, there was nowhere near enough time to incorporate all of these activities into my life meaningfully.

Now, several days a week, you can find me on a court with college students at least ten years my junior speaking in fast, unrelenting, slang-riddled French quickened by the urgency of running drills or trying to win a match. Through the women’s handball team, I often find myself right at the edge between pain and discomfort, exactly at the narrow line that separates intensive change from cognitive overload. Even though I still don’t quite get the rules and I understand maybe fifty percent of what is said at practice, this is how deep learning occurs. To engage all of your senses to learn while doing produces lasting results, but it’s most important to recognize that the regular engagement, imperfect as it may be, is where change transpires. If you say “yes,” to everything there’s simply not enough time to cultivate those yes’s, the process becomes a perfunctory chore and the results will be underwhelming.

The handball team that is graciously willing to pretend I’m not a decade and a half older than most of them while also tutoring me in French.

Change at Any Age

I will celebrate my 35th birthday in a few weeks. With a decade of a fully formed prefrontal cortex behind me, I can say that the experiences of my past ten years have certainly stretched and shaped my way of thinking. In those years, I learned to fly airplanes, write speeches for the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and even speak a little French. Still, the biological truth remains unchanged that our bodies and minds place certain contours on how we can expect to change as we age. Within that realization lies an opportunity, however, that the more we invite change into our lives – selectively and strategically – we can grow as decision-makers and both reframe and refine how we perceive the world. Change, regardless of the goal or circumstances that drove you to it, is a skill itself. So regardless of your age or if you’re set in your ways or not, you can learn to change.

Jennifer Walters is an active duty Air Force pilot serving as an Olmsted Scholar in France.