LSCO Lessons from Grant’s Overland Campaign of 1864: Preparing for Protracted Conflict

By Brigid Hickman

Within the past several years, Ulysses S. Grant has enjoyed a renaissance moment in the American collective memory. Biographies published in 2016 and 2017 by Ronald C. White and Ron Chernow, respectively, along with the 2018 release of The Annotated Memoirs of U.S. Grant by Elizabeth Samet and the May 2020 History channel docu-drama ignited a national reconsideration of this lieutenant general’s place in American history. In December 2023, President Biden and the U.S. Congress weighed in on the discussion and conferred the title “General of the Army” upon Grant through the National Defense Authorization Act, making him one of only three generals (along with Wasington and Pershing) to receive that honor.

Beyond serving as a sterling example of perseverance and bold risk taking, Grant’s leadership offers several lessons for leaders today as the U.S. Army prepares for large scale combat operations (LSCO). His 1964 Overland Campaign provides a useful case study in leading an organization through protracted, sustained combat across multiple battles.

When Lieutenant General (LTG) U.S. Grant assumed command of the Union Army and established his headquarters in the eastern theater with Major General (MG) George Meade’s Army of the Potomac, he left behind the trusted subordinate commanders (including MG William T. Sherman, William F. Smith, and James B. McPherson) with whom he achieved significant victories at Forts Henry and Donelson, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga. Not only would Grant operate in an entirely new theater with new Army and Corps commanders against the mythically superior Robert E. Lee, he also came into his new role as the first three-star general since George Washington. Although this rank provided him inherent positional authority, he still had to build trust with his skeptical subordinate commanders who possessed over three years of combat experience against Lee. Grant also had to change the organizational culture of the Union Army to prepare it for sustained and active campaigning. The expectation of a decisive Napoleonic victory over the Confederates would not materialize in 1864 nor at any other point in the Civil War.

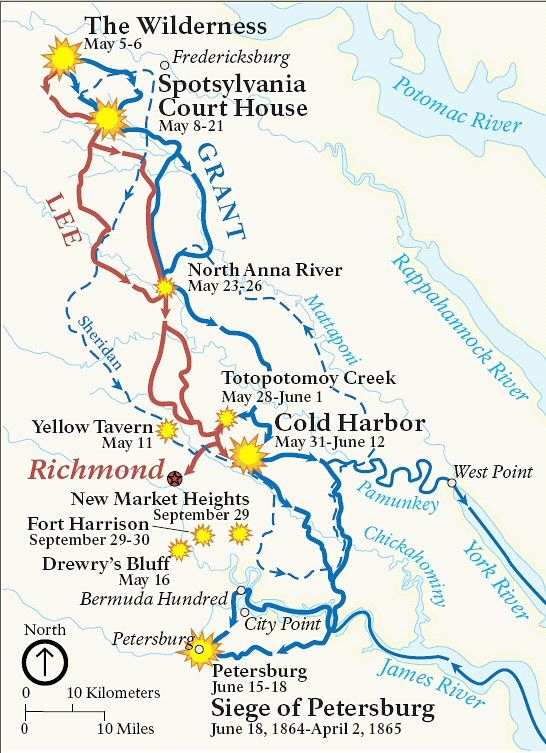

But his subordinates soon recognized that Grant’s strategy and leadership were distinctly different from his predecessors’. Whereas Hooker retreated from Chancellorsville and Meade failed to pursue Lee after Gettysburg, Grant refused to pause or withdraw after suffering tactical setbacks. Rather, from the Wilderness he chased Lee to Spotsylvania, and from there to the North Anna, and yet again from there to Cold Harbor. These successive battles set conditions for the siege of Petersburg, eventually forcing Lee to decide between preserving his army and defending Richmond. His choice of the former would ultimately lead him to Appomattox.

With the goal of winning the war by the end of 1864, Grant devised a strategy to defeat the Confederate Army by simultaneously engaging it in the western, southern, and eastern theaters. This would prevent Lee from moving troops back and forth between theaters to reinforce one another, and would also play to Union advantages in manpower and material. Grant’s strategy for Virginia: (1) charged Meade’s Army of the Potomac with neutralizing Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia; (2) tasked MG Butler’s Army of the James to advance up the James River towards Richmond; and (3) ordered MG Franz Sigel’s Army to attack Confederate forces and destroy its military supplies in the Shenandoah Valley. Positioned with Meade’s Army of the Potomac, Grant envisioned the Overland Campaign as a series of sequential battles that would attrite Lee’s army over time, restrict his movement within Virginia, and ultimately result in a Union attack against the Confederate capital at Richmond.1

The campaign commenced on May 5 with the Battle of the Wilderness. Although Grant outnumbered Lee nearly 2:1, two days of intense fighting with high casualties proved inconclusive. Mistakes by Union cavalry and lack of coordination between Union commanders provided openings for Lee’s characteristic boldness to compensate for his numerical inferiority. On May 6, when it appeared Lee’s army would be captured, General James Longstreet’s Corps arrived just in time to reinforce and rout the Union. Lee quickly counterattacked and pushed the Union forces back to their day 1 positions, gaining space and time to refit and relocate.2

Undeterred by this outcome, Grant pushed the Army of the Potomac further south in an attempt to turn Lee’s right flank. The armies clashed again the next day at Spotsylvania Courthouse, a battle that would continue for the next two weeks and feature some of the war’s most violent close quarters combat. Heavy rain created muddy fields, roads, and trenches and frequently prevented weapons from firing. Confederate forces constructed extensive earthworks that the Union was unable to penetrate, despite multiple frontal attacks. At the end of two weeks, both sides declared victory as the Confederates held their line and the Union inflicted significant casualties on Lee’s army.3

Grant continued his pursuit of Lee, heading south towards the North Anna River. Here, the armies would battle from May 23-26. Lee had dug in his forces on the south side of the river in an “inverted V,” forcing Grant to divide his army. Although General AP Hill did isolate the Union V Corps, the Confederates failed to destroy that corps or isolate any others. Lee became bed-ridden with dysentery in the final days of the battle and was unable to direct his army to consolidate its gains. After another iteration of see-saw combat, Grant once again withdrew and maneuvered south towards Richmond in an attempt to turn Lee’s flank.4

The next major battle occurred at Cold Harbor, a critical road juncture 10 miles north of Richmond, from May 31- June 12. This battle, perhaps more than any other, has contributed to the stereotype of Grant as a “butcher” because of his decision to launch a second frontal assault on June 3. By this point in the campaign, Grant had demonstrated his agility and maneuverability, while Lee showcased his engineering prowess with the speed and near impenetrability of Confederate earthwork construction. After Union cavalry under General Philip Sheridan captured the Cold Harbor road juncture on May 31, Confederates dug in and successfully repelled repeated Union attacks. At 4:30AM on June 3, three Union corps assault the Confederate earthworks but become trapped in the swamps, ravines, and thick vegetation in front of the Confederate positions. An estimated 7,000 Union troops die or are wounded in the first 30 minutes of the assault. The Union continues attacking throughout the morning, but Confederate artillery and canalizing terrain turn the battle into a massacre. Although Cold Harbor ended in Confederate victory, Grant continued his southern movement towards Petersburg and ordered Sheridan’s cavalry to destroy the Virginia Central Railroad. Grant succeeds in masking his movement from Lee for several days until they meet again at Petersburg.5

Despite initial Union setbacks at these main battles of the campaign, Grant maintained persistent pressure on Lee and restricted the Confederate Army’s maneuver space to narrow corridors in and around Richmond. Countless historians and military professionals have criticized Grant’s tactics and judgment during this campaign. But if modern day observers judge the campaign’s success by its outcomes, Grant’s strategic acumen comes into focus. His analysis of Lee as a commander and of the Army of Northern Virginia’s capabilities and limitations, when paired with his assessment of Union comparative advantages, informed his risk calculus. Grant deduced that the Union’s superior numbers and the depth of its defense industrial base could sustain an attritional campaign designed to force Lee to submit to his will. As time went on, Grant understood that his strategic objective was not the complete annihilation of Lee’s army, but an intense pursuit which would prevent it from ever seizing the initiative again. In Grant’s subsequent Petersburg and Richmond campaigns, Lee remained on the defensive and could not execute the offensive operations that had defined his success in the war’s earlier years.

Grant maintained his focus on his strategic objective despite perennial expectations from the public and federal leadership that a decisive battle would end the war in 1864. Although Lincoln implicitly trusted Grant, the commander-in-chief faced an uphill re-election battle that year as his Republican party fractured over the conduct of the war and the Democrats hoped to negotiate a peace agreement with the Confederacy. Here, Grant exemplified best practices in civil-military relations as his post-Spotsylvania promise to Secretary of War Stanton and General Halleck affirmed he would “fight it out on this line if it takes all summer”6 and reassured Lincoln of his commitment to the strategy.

With these insights, today’s Army can prudently plan and prepare for the demands of protracted conflict in LSCO. One consideration is that the American public’s appetite for sustained conflict may not match the realities of the strategic environment. Twenty years of the Global War on Terror culminating in the collapse of the Afghan government and military has taken a toll on our nation’s willingness to engage in another protracted conflict. And after 16 months of stalemate in Ukraine, most observers have been disabused of hopes for a decisive battle to end the war. If this war is any indication, modern LSCO conflicts will not quickly yield decisive victories. Considering this and the elusiveness of decisive battles in the Indo-Pacific during World War II (aside from the Battles of Midway and Guadalcanal), today’s Army leaders should prioritize the critical thinking and mission analysis necessary to channel Grant’s strategic acumen in determining campaign objectives. Analysis of relative combat power and comparative advantages should inform campaign design and risk assessments.

Grant’s current renaissance moment in American history is an overdue reexamination of a talented but imperfect, humble but complex man who overcame significant personal and professional failures, alcohol addiction, and depression to lead the Union Army to victory and, with Lincoln, to save the Union. His leadership presence and perseverance are just two of many qualities today’s Army officers would benefit from studying and emulating to prepare for the likely protracted campaigns of the next war.

About the Author:

Brigid Hickman is an active duty Army intelligence officer currently enrolled at Command and General Staff College en route to 7th Special Forces Group (Airborne).

Opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not represent those of the United States Army, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

Endnotes:

- Gordon Rhea, “The Overland Campaign of 1864: Dodging Bullets,” in Hallowed Ground, Spring 2014, re-published by The American Battlefield Trust, The Overland Campaign of 1864 | American Battlefield Trust (battlefields.org).

- “The Wilderness,” The American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/wilderness.

- “Spotsylvania Courthouse,” The American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/spotsylvania-court-house .

- “The North Anna Campaign,” The American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/north-anna .

- Gordon Rhea, “The Overland Campaign of 1864: Dodging Bullets,” in Hallowed Ground, Spring 2014, re-published by The American Battlefield Trust, The Overland Campaign of 1864 | American Battlefield Trust (battlefields.org).

- Ronald C. White, American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant, (New York: Random House, 2016), 353.