Learning from Our Adversaries: Leadership Lessons from the East Africa Campaign of GEN Paul Von Lettow-Vorbeck

By Brian Fiallo

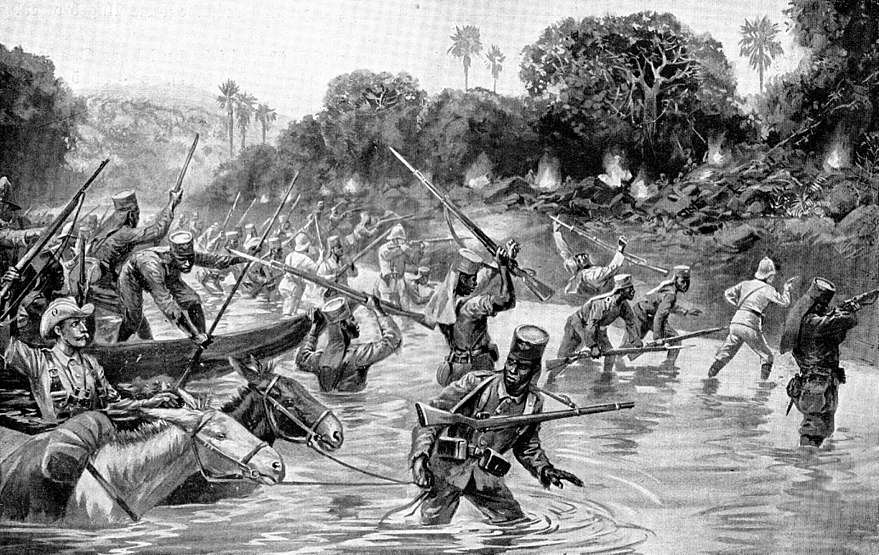

It is often the case that within professional development programs and schools run by the United States Army, the historical examples and case studies on leadership tend to myopically focus on solely American leaders. Of course, there is the occasional glance at allied leaders such as Field Marshal William Slim and his Burma campaign, yet these are the exception rather than the rule. I submit that there is much to be gained from a study of traditional adversary leaders and their campaigns, particularly now that much of the same ground in Ukraine being fought over now was fought over on the Eastern Front of World War II. During my spring break from the Command and General Staff College, I re-read the book African Kaiser by Robert Gaudi, which is a biography of one of my favorite figures in military history. General Paul Von Lettow-Vorbeck, who as a Lieutenant Colonel was the commander of the German Schutztruppe, or defense forces, of the German East Africa colony which is now modern-day Tanzania. Although he was born into the Junker class of Prussian aristocrats and could trace his military pedigree back almost one thousand years to the Northern Crusade of the Teutonic Knights, Von Lettow was very much the “soldier’s general” that we associate with the likes of General of the Army Omar Bradley, sharing extreme hardships with his men while leading the world’s first truly racially integrated army (Gaudi 2017, 222). Against a numerically superior foe that outnumbered his command at times by ten-fold, Von Lettow led a fighting retreat and guerilla campaign that stretched hundreds of miles, tying down inordinate amounts of precious Allied resources in what otherwise would have been a simple backwater campaign. From his campaign, I gleaned three lessons that I have used in past professional development sessions with my subordinate officers that I wish to share here now:

- As leaders we must understand where our operation fits within the larger strategic picture

- We must be innovative and use all the resources at our disposal, and last but certainly not least

- We must bear the hardships our soldiers face with them and not hold ourselves above discomfort or danger.

As Germany’s last remaining colony after the British and Allied forces quickly invaded and conquered the rest of Germany’s colonial possessions around the world, German East Africa (GEA) had little inherent strategic value. It was isolated from the rest of the German war effort and did not contain natural resources that could turn the tide of the war. Its strategic value, assessed Von Lettow, lay in its ability to tie down tremendous amounts of Allied resources that could therefore not be employed against Germany in Europe should the garrison continue the fight (Gaudi 2017, 148-149). Thus Von Lettow directed his campaign with the preservation of his force as the main objective, for as long as the German banner was raised in Africa, the British would be forced to devote resources to dealing with him. These resources at one point numbered 300,000 soldiers which could therefore not be directed to the war in Europe, or in perhaps an even more tragic circumstance, Gallipoli. The lesson here is that as leaders we must understand that the operation in our charge is not always going to be the decisive operation, main effort, or be the focus of our higher command’s support. Nonetheless, our operations may be vital shaping operations or supporting efforts which enable the success of the main effort, and thus are nearly as important to the accomplishment of the overall mission.

General Paul Emil Von Lettow-Vorbeck

Due in large part to its extreme distance from European Germany and the inability of the Kaiserliche Marine to break the allied blockade of Germany, Von Lettow’s force had to operate with only the means currently at its disposal. Although the Germans concocted a scheme to send the zeppelin L59 laden with supplies on what would have been the longest journey ever attempted by an airship to that point, the Schutztruppe did not receive these supplies and instead had to make do with what they had. They demonstrated resourcefulness through the repurposing of the light cruiser SMS Königsberg as a specific example. This ship was scuttled in the Rufiji River following a battle with the Royal Navy, and Von Lettow used its large naval guns as land-based artillery and its crew as infantry (Gaudi 2017, 318-319). As his supply situation worsened, Von Lettow continued his war by leaving German East Africa and invading Mozambique, then known as Portuguese East Africa. The Schutztruppe easily defeated the Portuguese garrison of a supply depot and rectified their supply problems for the duration of their campaign. The lesson gained from Von Lettow’s innovative approach is that while logistics are crucial to the successful prosecution of a campaign, we can prolong our operational endurance through applying the Improvisation Principle of Sustainment. Conveniently, the Army uses FM 4-0 for Sustainment and defines Improvisation as “the ability to adapt sustainment operations to unexpected situations or circumstances affecting a mission” (FM 4-0, A-2).

The last lesson I wish to offer from the portion of the Great War fought in East Africa is the value of an officer bearing common hardship with his soldiers. Throughout the campaign, Von Lettow bore the same deprivations that his subordinate German officers and black askaris faced. Although he was wounded and lost an eye in the campaign to suppress the Herero Rebellion in German Southwest Africa (Namibia) in 1904, he was never far from the front in East Africa. On one occasion, a blast caused him to re-lose that eye, although now made of glass, before one of his dedicated askari soldiers dusted it off and gave it back to him (Gaudi 2017, 24). He also suffered several bouts of malaria during the campaign, but all the while remained with his force. The dedication he showed his men was evident by their term of endearment for him, Bwana Obersti “Our Colonel”, and the fact that when he returned to Tanganyika, which would soon become modern Tanzania, in 1953 he was greeted warmly at Dar es Salaam by 400 askaris that remained alive (Gaudi 2017, 417). Von Lettow’s approach to leading an interracial force was extremely progressive for his time, and after the rise of the Nazi Party Von Lettow made clear in no uncertain terms what he thought of Hitler when offered the ambassadorship to Great Britain, causing him to be surveilled until the end of World War II (Gaudi 2017, 415). His cordiality with friend and foe alike led him to be respected by his adversaries as well as the German public, and he remained lifelong friends with the South African General Jan Smuts who led the British campaign against him. From Von Lettow’s example we see the effect of caring for one’s troops and bearing equal hardship has on one’s command. Likewise, we would all do well to heed this lesson and demonstrate to the soldiers in our care that we are not above the danger, discomfort, and difficulty we ask them to face.

While Von-Lettow was by no means a perfect individual, we can still remark at his innovativeness and forward thinking which truly served as a force multiplier for his army in East Africa. By casting off the social mores of the day and integrating his army, placing white soldiers under the command of black NCOs for the first time in a European army, he greatly expanded the command and control abilities of his force to conduct a decentralized guerilla campaign. His use of every available resource and ability to mobilize the population of the colony, both African and European, against the British attack enabled his force to do what other German colonies could not. Likewise, students of military history and of leadership in adversity would do well to study his campaign in greater detail than I have offered here.

About the Author:

Brian Fiallo is an active duty Army Armor officer currently attending the Command and General Staff Officer Course at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.