Leadership Lessons From the Grave

While my Dad attended CGSC and SAMS at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, my family lived just a few houses down from where I lived as a CGSC student twenty-five years later. One Saturday in the early fall of 1995, Dad finally relented and agreed to take me hunting with him (though I suspect the prospect of early youth deer season helped). In the woods and fields hunting deer, quail, pheasant, duck, and dove, Dad taught me about the fragile line between life and death. He laid the groundwork in the fall and winter of ’95 for the many lessons he would teach me the rest of my life. Patience, perseverance, and respect are tenets that were directly related to me through hunting. When Dad passed away last year, I had immediate regrets about the time lost not actively seeking his advice. Yet, as I retraced my childhood steps in Fort Leavenworth, I realized he has taught me much more than I previously suspected.

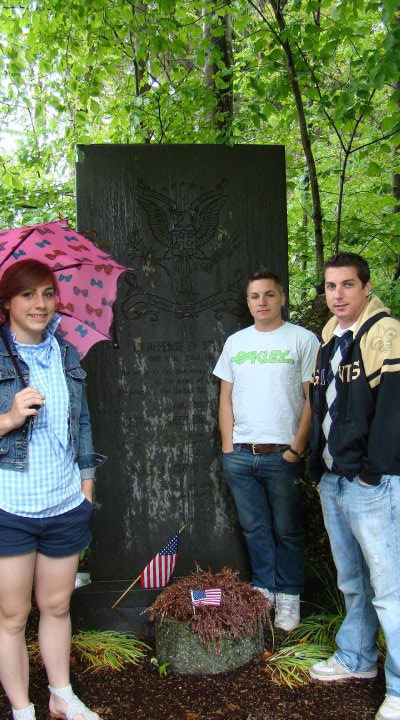

My father, Jim Wasson, was a radio DJ in Hammond, Louisiana and earned his bachelor’s degree in American History before joining the Army. He attended Officer Candidate School and commissioned as an Air Defense Artillerist, later becoming a strategist. The greatest soldier-scholar I’ve ever known; he never missed an opportunity to hone his craft. Growing up, my parents carted my siblings and me to battlefields around the world to learn about the decisions of combat leaders great and small. Walking the fields at Gettysburg, Chancellorsville, Mobile Bay, and Foy, he would help us understand the role that command decisions and visceral emotions can play in combat. In the evenings, I could find Dad buried in Grant’s memoirs, Washington’s letters, Napoleon’s correspondence, or Jomini’s thesis. His lifetime of study gave him a unique and keen insight into the military art. It was common to see him scribbling a letter to a friend detailing his latest maneuver in a long-distance tabletop wargame. When he bought our first computer-based wargames, Dad would teach me “lesson” after “lesson” by enveloping me at Austerlitz or letting me rush the attack at Gettysburg.

I readily admit that I am a poor substitute for my father when recounting his lessons. I have neither his ability to construct prose nor his capability to distill the complex into the simple. Notwithstanding my want of talent, I feel compelled to share his lessons that I rely on as a Leader. Much like Steven Pressfield’s fictional Alexander in The Virtues of War, “he has been much on my mind” and I often wish to “call upon his counsel.” When faced with pressing challenges and decisions (though admittedly none as serious as the Macedon mutiny at Hyphasis), I have fallen back on just a few of his simple lessons.

Patience, perseverance, and respect. The foundational values. Dad chose a simple setting to introduce me to these values, father and son, in the woods with silence, serenity, and nature for company. He continued to reiterate these values throughout my life. For Dad, patience was a virtue that required wisdom. To be patient requires an understanding of the complexities of a situation, the options available to an opponent, and what minimum information is required to make a good decision. He believed that perseverance was the hallmark of being tough. It wasn’t how hard or often you were knocked down, but how you responded. Growing up, Dad modeled respect for me. He showed me how respect for life manifests itself into a duty. He put this into action by being a dedicated Soldier, a faithful citizen, a devoted husband, and a great father.

Be fair, but tough. Coming home with a bloody nose after my first fight, my Dad asked a simple but important question. Who started it? After receiving confirmation that I wasn’t the instigator, he asked if I won. It was a powerful lesson. He explained I should never be eager to start a fight, but I should finish it. He would later expound upon this point by making this simple maxim applicable to more than just schoolyard brawls. Leaders must be fair, but tough. I called Dad for his advice prior to taking command and he reiterated his message as a foundational approach to leadership. Based on this advice, my first sergeant and I would set high standards and ruthlessly enforce them. To achieve this, we developed and published a document clearly articulating the standards and consequences for failing to achieve them. Applied uniformly, it provided Soldiers with clear expectations and goals.

The 4 Rs of Leadership. When I took my first leadership position in college, I called Dad to ask for his advice. In a manner that exemplified his philosophy, he took the complex and made it simple. His advice for good leadership was straightforward: Get your Soldiers to the right place, at the right time, in the right uniform, and with the right attitude. This was the essence of what Dad taught me about leadership. No matter how complex the situation, no matter how difficult the mission, a leader’s job is simple. His counsel allowed me to provide guidance to my new subordinate that wasn’t overly restrictive and enabled him to excel. By focusing on the end state (4Rs) and not the method, I could build engagement with my subordinates. I later applied his advice as a company commander, instituting a work call formation that allowed my leaders to ensure our Soldiers were in the right place, at the right time, and in the right uniform. The formation also provided an opportunity for my first sergeant and me to speak with the Soldiers before the day’s activities to ensure they had the right attitude.

Be cautious, but not timid … don’t act in haste. Just before deploying, I received a handwritten note in Dad’s typical chicken scratch on a spare bit of National War College stationery. I’ve carried this note for the last seven years. Dad’s advice could not have been more impactful to a junior leader navigating combat for the first time. He wrote, “Be cautious, but not timid … don’t act in haste.” With this advice, I’ve become adept at taking a “tactical pause” to ensure the risk I am assuming is prudent. Leaders must take bold action, but not excessive risk. I thought about Dad’s guidance after receiving intelligence of an imminent ambush against my platoon. The need for caution was obvious, but the warning against timidity was pertinent. Quickly my platoon sergeant and I developed a plan to flush the ambushers out to enable us to continue our operation. The situation required us to take pause, consider our circumstances, and take bold action.

The enemy has a vote. The last words of Dad’s note encouraged me to “remember the basics and think of everything the enemy can do. He does have a vote in things.” Too often leaders get focused on the variables they can control and fail to account for those they can’t. The enemy is an uncontrollable variable. I rolled my eyes at his cliché until I found my platoon’s patrol base cut off by the local Taliban we were fighting. As our CAB air dropped fuel blivets, suddenly I recalled Dad’s advice. I evaluated the terrain from the enemy’s perspective and considered his capabilities. After thinking through enemy courses of action, I could understand how he had shaped the battlefield. With Dad’s advice in mind, I could fully appreciate my predicament and develop a solution. I quickly put together a reconnaissance plan and developed courses of action to bypass the enemy’s obstacle. His advice was simple and cliché, but once again proved true.

These few lessons stand out in my mind for their simplicity and truth. While Dad also imparted lessons on the indirect approach or methods for determining the enemy’s center of gravity, it is the simple lessons to which I return. As I contemplated the most important lessons to share, I had an unshakable feeling that Dad would urge me to keep it simple. That was his style. Distill the complex until it becomes understandable. He embodied this philosophy in his daily life. In his last year, Dad would find exhilaration in an unassuming family dinner and playing guitar on the porch. Keeping it simple.

Dad freely shared his knowledge and mentored a generation of leaders. He continues to mentor me now. When I stumble across his CGSC and SAMS monographs I get a sense of how he approached historical analysis. As I read books from his library, I discover his margin notes with giddy joy. The passages he highlighted or underlined puzzle me at times, but I relish the opportunity to reconstruct his thoughts. I hope Dad’s words can continue to help inspire and train a new generation of leaders. Leaders capable of thinking critically, leading fairly, and keeping it simple.

Thank you, Dad.

Beau Wasson is an active duty Army Engineer officer serving as the Construction Officer of the 130th Engineer Brigade in Schofield Barracks, Hawaii.