Five Leadership Lessons from George C. Marshall

By Brigid Calhoun

Have you ever read a book that left such a profound impact upon you that you can’t stop talking about it? For me, that book has been David L. Roll’s George Marshall: Defender of the Republic (Caliber, 2019). I first encountered it last summer as assigned reading for a professional development fellowship in Washington, D.C. I must admit, I did not begin reading until a week before Mr. Roll was scheduled to speak to our cohort. But once I started the book, I could not put it down.

In learning more about George C. Marshall over the past year, I have become increasingly convinced that Marshall is the type of American military leader we need today.

George Marshall’s life story is impressive on its own, but Mr. Roll’s thorough research (which includes newly discovered personal correspondence), captivating writing style, and focus on Marshall’s interior life and character made this book an absolute joy to read. In learning more about George Marshall over the past year, and even visiting his Dodona Manor home in Leesburg, Virginia, I have become increasingly convinced that Marshall is the type of American military leader we need today. Of course, General Marshall is no longer with us, but those of us in uniform can still emulate his best qualities and accomplishments. While numerous book reviews thoroughly laud and critique Mr. Roll’s biography, in this essay I merely wish to share the five leadership lessons I gained from reading George Marshall: Defender of the Republic.

- Character Counts, and So Does Your Interior Life

Two themes Mr. Roll traces throughout the book are the development and steadfastness of General Marshall’s character and interior life. For a biographer to focus on a leader’s character is not uncommon—certainly Marshall’s character distinguishes him as one of the most consequential 20th century leaders. But the exploration of Marshall’s interior life struck me in a particularly compelling way. Mr. Roll explains: “Marshall lived by a moral code that emphasized self-control, perseverance, integrity, truth, honor, and duty.”1

Mr. Roll also describes Marshall as “magnanimous,” or “great-souled,” a description not often given to valorous military leaders. Marshall’s sense of discipline, knowledge of right and wrong, and faith in God underpinned his interior life. Even for non-religious and non-spiritual service members, Marshall’s moral clarity and trust in something bigger than himself remain poignant examples to follow. Ultimately, Mr. Roll’s powerful case study of this leader led me to consult other books about the interior life, most notably Jacques Philippe’s Interior Freedom. Reflecting on how a rich inner life can strengthen military resilience has been a fruitful by-product of reading both books.

2. Don’t Be Afraid to Speak Truth to Power

Despite Marshall’s commitment to self-discipline and military decorum, he did occasionally lose his temper. And several times, he lost his temper with a superior officer. But the context of these rare breaches in Marshall’s military bearing usually involves him speaking truth to power.

The first example Mr. Roll cites occurred in October 1917 in France, when then-Captain George Marshall served as the operations officer for the 1st Infantry Division, commanded by General William Siebert. During the division’s pre-deployment validation exercise, General John Pershing, the commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces, “dressed down” General Siebert in front of the entire 1st Infantry Division staff for the unit’s poor performance and sluggish mobilization. As Pershing turned to leave, an angry but resolute Captain Marshall grabbed his arm and gave the allied commander an earful about the resource requests his own staff had denied the division. While most of Marshall’s peers thought he had committed career suicide, General Pershing was impressed by Marshall’s candor and assertiveness. Pershing invited Marshall to a longer discussion of training, resourcing, and war strategy, and eventually hired Marshall as his aide-de-camp for six years.2 Their friendship would last a lifetime.

General John Pershing and Major George Marshall in touring French battlefields in 1919

Marshall spoke truth to power on several other occasions, mostly notably in how he conveyed his best military advice to his wartime commanders-in-chief, Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman. Aside from sternly correcting President Roosevelt when he collegially addressed the general by his first name (a mistake that Roosevelt would not repeat), as Chief of Staff of the Army, Marshall was the only advisor who disagreed with Roosevelt’s initial aircraft production and ground force generation plans in the fall of 1938.3 Marshall gradually built a broad coalition of support for his own plan, which scaled back on the number of planes and prioritized troops, weapons, and industrial capacity.4

Marshall later had similar disagreements with President Truman. The most memorable occurred after the war in May 1948, when their diverging views on foreign affairs led Marshall to yell “I would vote against the president!” at Truman–a proclamation that startled a president already suffering from low polling numbers during an election year.5 But Truman retained the highest respect for Marshall during his presidency–so much so that he would personally drive from the White House to Marshall’s home in Leesburg to consult the general. Imagine a President doing that today!

The lesson here is not that it’s okay to lose your cool on superior officers or commander-in-chief. There is a difference between forfeiting your military bearing and manifesting righteous anger in a tactful manner. But Marshall’s performance and reputation repeatedly earned the trust, confidence, and respect of his superiors to such a degree that when he spoke candidly, and even irately, they listened.

3. How to Spot and Manage Talent, with Humility

Perhaps a lesser-known fact about Marshall is that he served as the commander of Fort Benning’s Infantry School in the interwar period, an assignment he enjoyed enormously. Aside from the myriad opportunities it provided him to mentor and be around junior leaders, the command allowed him to assess company-grade officers’ talent and develop career-long relationships with them. Mr. Roll recounts that “in Marshall’s four and a half years running the Infantry School at Ft. Benning, 50 of his instructors and 150 of his students were destined to become World War II generals.”6 Some notable Marshall mentees included Omar Bradley, “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell, “Lightning Joe” Collins, Matthew Ridgway, and Courtney Hodges.7

Marshall thrived at Benning and discovered a military family he would cherish for the rest of his life. Perhaps the experience, and the men he mentored there, left such a profound impact because of how Marshall’s own talent was managed in assigning him to the post. In the year prior to his arrival at Benning, Marshall lost his first wife, Lily, and his mother. His father had died two years prior, and he was estranged from his only brother. Marshall was alone and teetering on an emotional brink.

His life-long mentor and friend, General Pershing, advocated for him to be assigned to Benning following the devastating deaths of Marshall’s parents and wife. Pershing understood what conditions and type of community Marshall would need to grieve and heal–a touching example of emotional intelligence, care, and empathy for a subordinate. Marshall paid this leadership forward to the 200 WWII general officers he mentored and nominated for combat commands during the war. Marshall himself never commanded in combat. Even when President Roosevelt offered him command of Operation Overlord, he humbly signaled that Dwight Eisenhower would be the better choice. Marshall later sent Eisenhower the original copy of the orders the president signed appointing Ike as the commander of the D-Day invasion, simply telling Ike that he thought he’d appreciate the memento.

4. How to Serve the Nation, but Not at the Expense of Your Family

As mentioned in the second lesson learned, George Marshall was not exempt from family tragedy. But at Ft. Benning, he found more than a military brotherhood. Through a close community of friends, Marshall met, fell in love with, and eventually married Katherine Boyce Tupper Brown, a widow from Baltimore. Marshall and his first wife, Lily, never had children. But after asking permission to marry their mother, Marshall became the devoted step-father to Katherine’s three children: Molly, Clifton Jr., and Allen. Both sons served in the Second World War, and although Marshall mentored them, he never interfered in their careers. Tragically, Allen was killed in Italy in May 1944 as part of the Anzio breakout. Marshall received the news just as the D-Day invasion was about to commence.

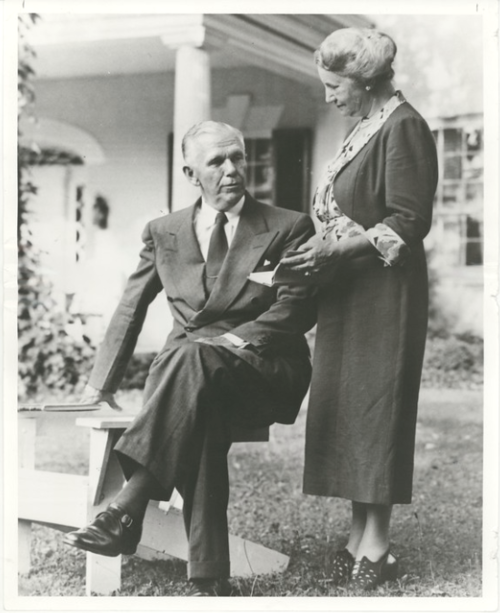

George and Katherine Marshall, Dodona Manor, 1951

Despite yet another devastating loss, Marshall remained completely devoted to his surviving family. Even during the most trying periods of the early war, Marshall would ride his horse from the War Department to his home on Fort Myer to have afternoon tea with Katherine, often with his dog trotting alongside. He always made time for Molly, Clifton Jr., and their families, as well as his surviving sister. Marshall also took up gardening when he and Katherine purchased Dodona in 1941. Today, visitors can still walk through his gardens, which are now maintained by the Leesburg gardening club.

5. Military Leaders Must be Apolitical

This fifth and final lesson from Marshall is perhaps the most salient for military leaders today. In an era of hyper-polarized politics, which seem to impact every facet of life and society, service members must remember that our oath is to the Constitution, not a political leader, and that we remain subordinate to civilian control of the military. We have perhaps become desensitized to this as we observe general and flag officers endorse political candidates or sign statements decrying elected officials. But we can find strength in Marshall’s example of apolitical military service. Marshall himself never voted in an election. While I do not necessarily advocate that all service members follow this particular practice, we can find wisdom in Marshall’s understanding that war and politics are inherently linked, as Clausewitz famously observed in the previous century. Mr. Roll explains further: “Marshall believed that involvement in partisan politics might conflict with his obligation as a military officer to subordinate himself to civilian authority and would undermine his effectiveness as Secretary of State and Defense.”8 Marshall felt a strong obligation to uphold the “sacred trust” of the American people, stating “[w]e…are member[s] of a priesthood really, the sole purpose of which is to defend the republic.”9

“[W]e…are member[s] of a priesthood really, the sole purpose of which is to defend the republic.”

GEN George C. Marshall

Aside from these five leadership lessons, civilian and military leaders at all ranks can benefit immensely from reading Mr. Roll’s biography of General Marshall. The reader is nearly guaranteed to learn something new about the only American to serve as both Secretary of Defense and Secretary of State. As Mr. Roll details in his epilogue, a good argument can be made for our consideration of George Marshall as “the only soldier-statesman in the history of America worthy of being compared favorably with George Washington.”10 Today, aside from perhaps former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, few leaders can claim such strong bipartisan support for being a truly apolitical defense professional. George Marshall’s life provides a compelling witness to the sacred trust our nation places in us, and our duty to defend the republic.

Postscript: On July 4th, Mr. David Roll will deliver a talk on GEN Marshall at Dodona Manor at 11:30AM. Entrance is free and open to the public. Further details can be found here.

About the Author:

Brigid Calhoun is an active duty Army Military Intelligence officer serving as a military assistant at the Pentagon as part of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Intern Program.

Endnotes:

- David L. Roll, George Marshall: Defender of the Republic, (New York: Dutton Caliber, 2019), 3.

- Ibid., pp. 19-21.

- Ibid., p. 113.

- Ibid., p.115.

- Ibid., p. 513.

- Ibid., p. 86.

- Ibid., p. 86.

- Ibid., p. 5.

- Ibid., p. 5.

- Ibid., p. 600.