Getting the Headquarters ‘Platoon’ Right

Any United States Army soldier can tell you what the problem with his or her small unit is. Simply put, it usually begins with ‘those idiots up at platoon.’ The lieutenant, in charge of the platoon, likely would say ‘company is all messed up, that’s the source of our troubles.’ Company commanders will typically extort that ‘battalion has put out yet another last minute tasker, man they are always so jacked up.’ You get the idea. As ‘stuff’ proverbially likes to roll downhill, criticism inevitably ascends back up the hill.

As ‘stuff’ proverbially likes to roll downhill, criticism inevitably ascends back up the hill.

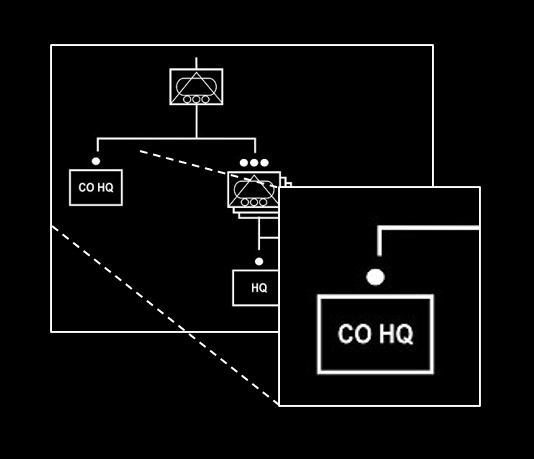

Company commanders have the unenviable position of carrying the water in between the first large unit of action within the Army (a battalion, which also, coincidentally, is the first unit in the Army that maintains its own staff) and the actual ‘doers’ of missions at the platoon level and below. Successful company commanders seek to strike a balance between being personable and professional. A carefully managed relationship with subordinates and higher headquarters is a choreographed dance that requires constant attention, but there is at least one tool that the company commander can leverage to make his or her own life a little easier. This tool is the organization sometimes called the ‘headquarters platoon.’

The perpetually undermanned, under-resourced, and overworked headquarters platoon is almost a trope within company level formations. It is incredibly challenging to ‘get the people right’ within this small organization. Typically composed of either excess soldiers or those who cannot physically fight, along with trade specialists such as the supply sergeant or communications sergeant, these small units can serve as a tipping point towards success for the company level formation.

Regardless of the function of the headquarters ‘platoon,’ (a likely misnomer given that this organization rarely breaks into the double digits personnel wise) it requires people to function. Unfortunately, given the variety of specialized tasks required, the people are usually hard to find within company level formations for a few key reasons.

First, moving a soldier to headquarters is seen as ‘a step down from the line,’ or perhaps it is regarded as a ‘place to stash the broken people.’ Truthfully, it should be neither of these things – however, it is difficult to argue with the logic that usually leaves it this way. After all, why take combat power away from the platoons to man an organization that does not directly need to load tank rounds or carry a rucksack in support of actual combat operations?

After all, why take combat power away from the platoons to man an organization that does not directly need to load tank rounds or carry a rucksack in support of actual combat operations?

Second, the table of organization and equipment usually limits headquarters personnel to two or three soldiers – all lower enlisted – and leaves limited room for leadership. Thus, the duties of the headquarters platoon sergeant often falls to one of several other already overworked noncommissioned officers. Depending on re-enlistment dates or permanent change of station timelines, this can be avoided, but it is never a truly static position within the company.

Both these issues coalesce into the third point, which is that there are needs placed on the organization that demand manpower, and company-level priorities are usually the lowest on the totem pole.

This leaves the commander in the hard place of ‘robbing Peter to pay Paul’ when it comes to headquarters manning. Nevertheless, the benefits of properly investing in headquarters personnel are unquestionable. Having soldiers who can quickly move the company command post, organize radio watches, or man security shifts help in tactical situations are all a boon to the company, yet the benefit extends beyond this. In truth, the company’s readiness can be greatly shaped by how the soldiers assigned to the headquarters platoon conduct themselves. Do platoon sergeants need to consistently walk items up to the battalion headquarters? Or rather could a routine system established by a company clerk alleviate this drain on time? Can the company store training ammunition in the arms room, or must it be guarded overnight? A good armorer would likely know how to best coordinate effort across the battalion to prevent soldiers from needlessly wasting their time.

In truth, the company’s readiness can be greatly shaped by how the soldiers assigned to the headquarters platoon conduct themselves.

In light of these problems, improving a headquarters platoon can seem like a daunting task for any company commander. However, a few simple actions can have a lasting impact.

Some Possible Remedies:

- Take a newly promotable specialist and assign him or her to be the company clerk. This up-and-coming specialist can be put in the first sergeant’s pocket, and after a year of an assignment in this position, will be better suited to be a team leader or equivalent status.

- When able, use a mid level noncommissioned officer that has already completed his key development time in his current rank to fill the leadership slot in headquarters. If in a unit that requires it, this soldier can also serve as the commander’s gunner in mounted formations. While this may be counterintuitive, taking a solid performer from a platoon to give them ‘company level’ experience is incredibly beneficial for that up and coming leader.

- Soldiers that have expressed interest in becoming a warrant officer or commissioned officer also fit this billet well. Positions within the headquarters platoon are generally more system or process focused in garrison, and becoming proficient at these basic tasks are likely to start this new officer off in the right direction.

- In general, as mentioned earlier, positions within the headquarters platoon need to be ‘framed’ as broadening, vice simply a position that is filled as a holding pattern for those exiting the Army or those who can’t ‘cut it on the line.’ This broad maxim makes it easier to empower those within the headquarters platoon to execute tasks on behalf of the company. Quality, especially within the headquarters platoon where each position is crucial, absolutely trumps quantity when it comes to headquarters manning.

- If possible, request an incoming 2LT from the battalion staff in order to have them lead the headquarters platoon. Not only does this give the platoon an actual person to ‘pin the rose on’ for leadership, it also adds another body who can help accomplish tasks within the organization. For their own development, it exposes the new leader to a company level organization, and they will be able to share positive (and negative!) lessons learned to other company level organizations within the battalion once they receive their permanent assignment. This assignment can even be temporary, based on either field problems or for specific short durations.

- Yet a further alternative is to have your executive officer serve as a de facto headquarters platoon ‘leader.’ This tactic has to be used very carefully, however, as your executive officer likely has many other tasks that he or she must accomplish on a daily basis, and ‘leadership’ especially within the headquarters platoon, will likely fall to the bottom of that lengthy list.

- Lastly, if the headquarters platoon simply cannot be manned to utility, the platoons must be empowered to work some of the functions of the headquarters platoon. Assign platoon leaders with oversight of the specialty positions such as communications or CBRNE noncommissioned officers, and enable the platoon sergeants to move administrative actions forward directly to your desk as required. In this case, the old adage of ‘putting a leader in between you and the problem’ can be fulfilled. Keep in mind, however, that this places additional risk on your organization’s readiness, given that the platoons will be focused on things outside of lethality or readiness.

Final Thoughts:

In keeping with the nature of this blog, the author wouldn’t be writing about this if he had thought that he had executed this delicate process perfectly during his time in command. Strong First Sergeants over the course of my commands absolutely prodded the organization in the right direction. Challenges remain in explaining to the rest of the soldiers in the company why these headquarters personnel sometimes were seen as receiving special privileges, or even keeping the motivation up of well meaning soldiers depressed about their assignment to the company headquarters.

In strengthening this part of the organization, the company commander can again focus on maintaining relationships laterally and with higher headquarters, easing the burden on the entire formation.

In conclusion, the company’s woes are not going to be immediately fixed with better soldiers occupying the headquarters platoon. However, a strong headquarters platoon enables the company commander and his or her subordinates to accomplish the mission without constant distractions. ‘Getting the HQ platoon right” also enables good systems and processes for “governing” the company. This provides further predictability and allows the unit to be proactive versus reactive, freeing up “decision space” for the commander. In strengthening this part of the organization, the company commander can again focus on maintaining relationships laterally and with higher headquarters, easing the burden on the entire formation.

Alexander Boroff is an active duty Army Major serving as an Army Joint Chiefs of Staff Intern on the Army Staff in the G-3-5-7. An Armor Officer, MAJ Boroff has commanded company formations in both the generating and operational force.