The 300-Meter Target for Motivation

By Tara Middlebrooks

What do you do when you, or someone you lead, does not have the motivation to do what they need to?

The Problem

Quite often the discussion first turns to the basics of intrinsic motivation (behavior driven by internal rewards) and extrinsic motivation (behavior driven by desire of external rewards or avoidance of punishment). It’s one thing to worry about these on an individual level for yourself, but solving the problem for a larger group that you are in charge of can be more complicated. Almost instinctively, leaders tend to start with extrinsic motivation, but find that it can only get you so far; you eventually realize you lack the resources, time, or authority to offer something with enduring substance. What does it mean if the organization only gets moving when there is an external reward? What do you do when the reward runs out? What alternatives do you have? How do you understand what is going wrong on the individual and group levels?

We have all heard phrases like:

- “If we finish X, Y, and Z tasks we can go home early.”

- “If you get the top Physical Fitness Test score in the company, you’ll get a three-day pass.”

- “Make sure you do X so you can put in on your NCOER/OER (i.e. evaluation) and get a top block.”

I’m not saying I wouldn’t appreciate any of those things, and sure, they work in the short term, but what is the long-term strategy? What do you do when there are no more parking spots to offer, passes to grant, or other externally driven motivators to distribute? Basic tenants of conditioning imply that when you remove the reward, over time, the desired behavior will ultimately fade away. Thus, there needs to be something else motivating people, something they value and can commit to. Maybe at this point you will start to think about approaches to intrinsic motivation, but that requires a much different approach—more time to work with individual motivations, work through tough conversations about abilities, interests, importance, etc.

In the Army, we routinely knock down so many 25m targets (what can just get the job done now so we can move on to the next dozen priorities) that we cannot see the 300m ones (thinking about how we can sustain these outcomes in the future). Long term reliance on extrinsic motivation can create a false sense of security in the commitment and productivity of the organization.

This is the cycle we need to break as leaders. How do we figure out what the root of the motivation problems are, both in ourselves and in others? Where can we most effectively target our efforts? Richard E. Clark, former president of Atlantic Training Inc and professor of Educational Psychology at the University of Southern California, developed a framework called the Commitment and Necessary Effort (CANE) Model that helps diagnose and solve motivation problems at work. This model can help provide a common language to problems and variables you’ve likely already experienced. Sometimes simply providing language to discuss a problem can help you dissect it in a way that makes it more manageable; it gives you a starting place to tackle a complex problem, like motivation.

The Framework

“Two motivation processes—committed, active, and sustained goal pursuit on the one hand, and necessary mental effort to tackle goal-related problems, on the other hand—are the primary motivational goals in the CANE Model.”2

To understand the fundamentals of the CANE Model, Clark1 suggests that solving performance problems is like examining a system of:

- Goals: Are they clear and specific?

- Knowledge: Does the person have adequate knowledge?

- Resources: Are necessary procedures, time and materials available?

- Personal Investment: Does the person have enough commitment and adequate effort in pursuit of the goal?

Regardless of the motivation problem—physical training performance, battling complacency in proper maintenance procedures and protocols (we all know those PMCS procedures get old after a while), working on an additional duty you have little to no interest in, following an order to complete priorities that don’t align with your own—there is a way to break it down and understand the root cause and find a starting place to tackle the commitment problems one at a time.

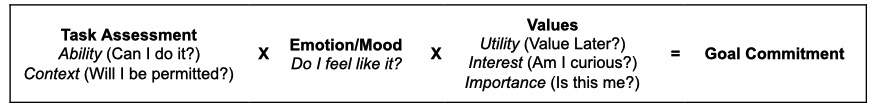

The three commitment problems discussed in the CANE Model are: Task Assessment, Emotion, and Values,3 each with their own set of questions to explore. These commitment problems are shown in the graphic below.

Applying the Model

Task Assessment: Ability (Can I do it?) & Context (Will I be permitted to do it?)

Our commitment is more likely to increase if we have the skillset to accomplish the goal.4 Commitment decreases if we doubt ourselves, or worse, if the organization is unwilling to let us use our skills appropriately. In the Army, we are well-versed in training key tasks and improving fundamental abilities. However, we struggle with the context: giving those we lead time and space to innovate and be creative with their unique expertise and abilities. We should aim to delegate to enable, not delegate to control.

As an Engineer Officer, if I am struggling on a construction site to get my team to meet certain deadlines, I may fall into a trap of micromanagement—asking for more updates on the schedule, materials, manning, and slowly absorbing more control over time. Micromanagement does nothing but stifle innovation and limit the growth of the NCOs that are running the job site. In the long-term, it can damage their own development.

As leaders, we not only want to make sure those we lead have the tools for success (abilities) but that we give them support and autonomy to take the initiative and try new things (context), that we support their ideas, and are willing to accept some level of failure (as that is inevitable) as we figure it out. As leaders, we own the responsibility to create the environment that will make the mission successful. Is there a process or a policy we can change? Any procedural barrier we can reduce? How can we empower people to believe they can be successful? What gap in training can we close?

Emotion/Mood: Do I feel like it?

Mood problems often take more work to develop than other commitment problems—it involves workplace culture and environment, leadership examples, and emotion-control. Intuitively, positive emotions facilitate commitment, while negative emotions discourage commitment.5 Often, we operate at high tempos and under high stress, which leads to more negative emotion and short tempers.

There will always be times where we don’t “feel like” doing something. Cleaning weapons, property inventories, certain administrative tasks, training in the rain…all things we know we have to do. As an individual, you may have your own rituals that make them tolerable, but what about the larger group? Think about ways you can assess and shape the culture and environment around the group. Music in the motorpool or while cleaning weapons? Predictability in fundamental tasks and expectations? Expressing gratitude regularly? Positive self-talk? Modeling positive emotions as a leader? Clark6 indicates the leaders and teammates have tremendous power and influence in modeling coping behaviors and emotional control.

Leaders and teammates have a positive impact on others in the organizations and can increase commitment to organizational goals. Leaders set the tone for everyone else around them. What tone are you setting? What example are you providing in the words you choose, the non-verbal cues you’re providing, how you prime the conversations you have or orders you give? How are you rewarding a job well done and providing feedback on improvements?

Every action you make as a leader contributes to a workplace culture that motivates people and enables them to thrive. Be the force that inspires tjat culture to those you lead. They are waiting for your positive example–and they will notice if or when it doesn’t come.

Value: Utility (Value later?), Interest (Am I curious?) & Importance (Is this me?)

Utility is achieved when a person does not value the task but values the consequence of successfully completing a task. If a task is ultimately valuable, a person will commit to it.7 Interest occurs when a person is curious or enjoys the pursuit of a goal, even if it does not make them successful or more effective. Satisfaction and commitment increase with the level of interest.8 Importance comes from recognizing a task represents a person’s strength or supports a personal goal.9 All three of these components contribute to overall value someone sees in a goal or task.

Clark10 explains that the value of a goal increases when employees perceive the goal as “assigned by a legitimate, trusted authority with an ‘inspiring vision’ that reflects a ‘convincing rationale’ for the goal [or task], who:

- Provides expectation of outstanding performance

- Gives “ownership” to individuals and teams for specific tasks

- Expresses confidence in individual and team capabilities

- Provides feedback on progress that includes recognition for success and supporting but corrective suggestions for mistakes

Leaders play a huge role in framing a goal or task to those they lead. Evaluating the three value components, as well as what helps employees perceive a task as valuable, will help you determine how to empower those you lead to get the task done. Reinforcing the utility could mean providing more transparency in why a certain task is important, what it could help the organization (or the individual) achieve. Provoking interest could mean helping them see how a task aligns with a goal or interest they have or capitalizing on an existing skill set.

As a Company Commander, if you have an Executive Officer that you know aspires to have your job one day, how can you assign and shape the tasks you provide him or her to highlight that it will help him or her achieve that goal? If you have a subordinate seeking progression in their field, how can you give him or her an added challenge or raise expectations to help him or her grow and achieve the next level of responsibility? If you’re an Engineer, you know your team leaders will one day be a Project NCOIC; what tools can you give them to keep them engaged, informed, and learning? Are you strategically assigning your tasks, aligning them with the strengths, interests, and importance of those you lead? You cannot do it in every case, but taking a few extra moments to figure out the right tasks for the right person (with regards to motivation) can enhance the organization’s performance as a whole.

Now What?

We’ve discussed the fundamentals of motivation, the key components of the CANE Model, and some application examples. Now what actionable steps can we take next time we notice ourselves, or our organization, struggling with motivation?

First, understand:

- Your own self-awareness: What culture have you created? What precedent has been set? What are your strengths, your weaknesses? Is there something you could be doing differently?

- Your people: What are their abilities? Strengths? Weaknesses? Interests? Concerns? What ideas do they have for the task or organization?

Second, ask the right questions:11

- Do you (or they) have the ability and/or knowledge to accomplish the task?

- Is there a barrier to your (or their) success that can be removed or modified?

- Is the environment conducive to your (or their) success?

- Is their utility in support of personal or organizational goals?

- Is there something unusual or intriguing about the task?

- Is it important to your (or their) personal goals and interests?

Third, prioritize:

- Which tasks provide the most impact to their motivation and the desired end-state of your mission?

- Work with your people to figure out the next steps. It gives them ownership of their own future and keeps you in the role of enabler, a space every leader should occupy.

Wrapping It Up

Working towards that 300m target means investing in development now, encouraging innovation now (i.e. avoiding the phrase “we’ve always done it that way” without putting thought into alternatives), asking the right questions to dig deeper in the relationships you have with your subordinates now. If you figure out what makes them tick, really get to know them, figure out what can get them truly motivated, your Soldiers will take more pride in their work and as a result, get that 300m success.

Looking back, I struggled a lot as a Platoon Leader with narrowing down the right way to approach motivation. I could not understand why some tasks and requirements were so difficult compared to others. Whether it was not asking the right questions, seeking more involvement from my subordinates, or customizing tasks when I could, I wish I had viewed motivation as a framework to dissect and develop 300m success, as opposed to an obstacle distracting me from a 25m task.

As leaders, and good teammates, we are enablers—whenever I focus on that goal first, I am always impressed by the outcomes of those around me and the motivation that comes with it.

About the Author:

Tara Middlebrooks is an active-duty Army Engineer officer serving as an Instructor in the Behavioral Sciences and Leadership Department at the United States Military Academy at West Point.

References: Clark, R. E. (1998, September). Motivating Performance: Part 1 – Diagnosing and Solving Motivation Problems. Performance Improvement, 37(8), 39-47.

- Clark, R. E. (1998, September). Motivating Performance: Part 1 – Diagnosing and Solving Motivation Problems. Performance Improvement, 37(8), 39.

- Ibid., 41.

- Ibid., 42.

- Ibid., 41.

- Ibid., 41.

- Ibid., 43.

- Ibid., 43.

- Ibid., 43.

- Ibid., 43.

- Ibid., 43.

- Ibid., 43.