Two Years Later: Contextualizing the Afghanistan Withdrawal through the lens of Viktor Frankl

By Giovanni Tomasi

August 20th marked the second anniversary of the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. Like many service members who served there I have at times struggled to rationalize the meaning of our 20 years of effort in that country. Despite the nine years between my deployment and now, the outcome of our calamitous military withdrawal from Afghanistan is still a bitter pill to swallow. Without judging the political decisions that led to the withdrawal, I find myself asking what did we all fight for? Why did my friends and comrades die on that distant battlefield only to see the Taliban regain power?

Some helpful perspective came from an unexpected source. During a recent counseling session with a superior officer, the topic of my deployment to Afghanistan came up in conversation. This officer reflected on his own deployment experiences over a 20+ year career and recommended I read Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl. He told me the book provided him with valuable wisdom that has allowed him to put his multiple deployments in perspective. I am thankful I took his advice and discovered that this classic does indeed offer valuable insight for contextualizing Afghanistan.

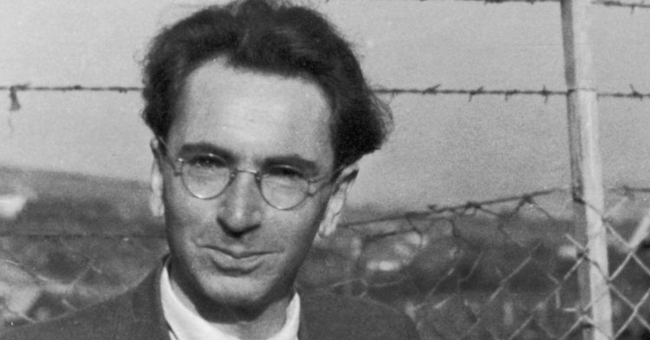

Dr. Viktor Frankl was an Austrian psychiatrist and holocaust survivor who founded the psychological school of logotherapy. Logotherapy focuses on finding meaning in one’s life as the primary human motivational force.1 Prior to the outbreak of World War II in Europe, Frankl worked in the field of psychiatry in several prominent hospitals around Vienna, with a specific emphasis on preventing suicide. During this period, he authored several papers and began the process of compiling the foundations of logotherapy. Following the Nazi occupation of Austria in 1938, Frankl found himself increasingly alienated in Viennese society as a Jew living under Nazi oppression. In 1942, the Nazis sent Frankl, his wife, and his elderly parents to concentration camps, from which only Frankl survived. Following this experience, Frankl wrote Man’s Search for Meaning in 1945 as a “concrete example that life holds a potential meaning under any conditions, even the most miserable ones.”2 In this work, he narrates how he survived the grotesque realities of life in the camps and the development of his psychological outlook, and synthesizes the main points of logotherapy for the reader to conceptually understand.

While the experiences of surviving the holocaust and military service in Afghanistan are absolutely incomparable, the book offered me profound insights on coming to terms with events in life that cannot be changed. The first key point was that of a purpose-driven approach to life. While this notion is far from novel for military members who live by “mission first and people always,” Frankl provides a different perspective from the military’s mission-oriented outlook. Purpose is not a task to complete, but instead is an outlook one must discover to ascribe meaning to their life. Frankl insists that there is no single meaning of life that is true for the entirety of a person’s lifetime but instead “the meaning of life differs from man to man, from day to day and from hour to hour.”3 As such, meaning can be derived by “(1) by creating a work or doing a deed; (2) by experiencing something or encountering someone; and (3) by the attitude we take toward unavoidable suffering.”4

The first method to derive meaning, to create work or do a deed, is familiar to military readers as something akin to mission-focused tasks. However, Frankl stresses the importance of his second method of experiencing something or encountering someone, with a specific emphasis on love. He offers the way to fully experience someone, or something, is through the act of love, and that this act itself can be one’s purpose. When using this outlook to understand service in Afghanistan (or any theater for that matter), the concept of love-the-act as a purpose is astute. When attempting to internalize the deeper significance for a deployment, it is tempting to deem anything short of total mission accomplishment as failure and the deployment as a waste of time. Instead, using the lens of Frankl we must shift our outlook and acknowledge our military service is ultimately an act of love; whether it be love of country, family, comrades, or the good in humanity. This act itself becomes the meaning of our service. As such, our time deployed was an act of love, and although in hindsight it did not yield the objective we were seeking, it was an act of love all the same. Does an act of love for a terminally ill person lack any meaning because that person will inevitably die? Certainly not.

The final method Frankl offers is through suffering. I recently had the opportunity to attend a reunion for my Troop that had deployed to Afghanistan in 2014. Out of the roughly 30 of us who attended, it was striking how many of my comrades continue to suffer deeply from psychological wounds. These wounds were not only from the combat itself, but also from the sense of loss felt after one of our brothers committed suicide well after deployment and in some cases the meaninglessness they felt after leaving the military. Many of them wondered what purpose their suffering had, if any, in the greater scheme of things. To this question, Frankl offers that when someone must endure suffering, they maintain the unique ability to “transform personal tragedy into triumph”.5 Human beings have the freedom to choose how they view a situation, which can itself liberate them from suffering by giving their ordeal meaning.6

This concept translates well into the context of military combat experiences. Many veterans proudly wear combat experience as a badge of honor, even as it psychologically defaces. This defacement can take many forms to include post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), nagging regret, nightmares, or flashbacks. However, after recognizing this, it is imperative not to dwell on the negative, but instead to acknowledge the positive experiences from deployment. These include the strong relationships, sense of community, jokes, humor, and fellowship forged between those who have lived through hardship together. I can remember a phone call I had with my family two months into my 2014 Afghanistan deployment. Understandingly, my family asked how “it was going” and expected to hear about the terrors of war given our unit’s assignment to an active area. I told them honestly that I had never laughed so much in my life. Instead of dwelling on combat, for me the reality of that moment was the comradery I shared with my fellow officers, NCOs, and Soldiers born out of the trust we had built with one another. Even now, many of those relationships persist– three of my closest friends today are from that deployment and continue to be my brothers in every sense of the word. For those experiences and relationships, I will eternally be grateful for my Afghanistan deployment despite the ultimate outcome of America’s twenty-year effort.

It is easy to read Man’s Search for Meaning and fail to see the connection between military service and the gut-wrenching horrors Viktor Frankl endured in the concentration camps. However, Frankl’s book speaks to the suffering that any human being may experience no matter the magnitude, and how from it, to ultimately find meaning in life. As veterans we don’t have to like how Afghanistan ended, but we must find a way to live with it. Frankl offers that “It doesn’t matter what we expect from life, but rather what life expected from us.” We should seek meaning in our service that we showed up and performed a profound act of love. We should acknowledge and focus on the positive experiences we gained from the experience of Afghanistan. I would offer that we, as veterans, need to remember that it was ultimately love that motivated us to serve and to strive to bring freedom to Afghanistan. That act of love was noble and good. Therefore, we should celebrate our service no matter the outcome of the mission.

About the Author:

Giovanni Tomasi is an active-duty Army Major. He previously served as an Infantry Officer in the 3d Cavalry Regiment, 3d U.S. Infantry Regiment (The Old Guard), and the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault).

Opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not represent those of the United States Army, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

Endnotes:

- Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2006) 97-99.

- Ibid., XIV.

- Ibid.,108.

- Ibid., 111.

- Ibid., 112-115.

- Ibid., 66-67.