Field Manual (FM) 3-0 Implementation Challenges

By Evan Bruccoleri

This assessment is a forward look at potential FM 3-0 implementation challenges for field grade officers at the brigade level and below. While this document is not intended to be a sophisticated review of FM 3-0, the three highlighted examples intend to 1) inform field grade officers that the new FM 3-0 published October 2022 if that is news to you, and 2) provide thoughts to navigate the future challenges that implementation of this new manual will engender. FM 3-0 dates its original history to the 1930s. The Army has subsequently updated operational concepts within several times to include after the 1979 Yom Kippur War, in 1986 ahead of Operation Desert Storm to reflect the “Air Land Battle” doctrine, in 2001 for “Full Spectrum Operations”, in 2012 for “Unified Land Operations”, and most recently in2017 and 2022 for “Multi-domain Operations” (MDO). The Army’s current version of FM 3-0 builds upon the MDO concept introduced in 2017, draws on all previous Army operational concepts, and proposes that theater and below commands implement this modernized concept.

Multi-domain operations are the Army’s contribution to joint campaigns, spanning the competition continuum. Below the threshold of armed conflict, multi-domain operations are how Army forces accrue advantages and demonstrate readiness for conflict, deterring adversaries while assuring allies and partners.1

Potential Challenges:

Army forces must accurately see themselves, see the enemy or adversary, and understand their operational environment before they can identify or exploit relative advantages.”2

(1) Ability to see yourselves.

How often do Brigade and Battalion units “see themselves”? It is hard to see ourselves well in garrison training environments until brigades receive professional support. Brigade collective training typically culminates in a visit to the National or Joint Training Center where permanent military evaluators utilize sophisticated methods to deliver feedback to rotational units, usually once a year. Divisions recently have gotten better at synchronizing brigades to provide observer support but otherwise brigade and below units rarely receive feedback on the unit’s performance and training. In the training plan that leads to a training center rotation, it is unlikely that brigade organic assets like reconnaissance, electronic warfare, or military intelligence tools conduct electromagnetic spectrum surveys of command posts and large maneuver elements to refine brigade internal procedures.

This framework places added demands on brigade and below tactical units because many of the units delivering MDO effects are not organically aligned under a Brigade Combat Team, hence the transition to the Division as the unit of action. This challenge will likely grow as the Army consolidates enabler functions at the Division level and makes it the nucleus of the fighting force. This separation of training and organic structure could impede the daily ability to gain competency within the Brigade. Although FM 3-0 floats no direct solutions to this problem, it is likely that relationship building and a leader’s desire to learn will continue to be a means to bear new capabilities for the brigade and below. Knowing this, field grade officers could evoke the “see ourselves” function of professional training more frequently as the Army implements FM 3-0.

War is the realm of uncertainty; three quarters of the factors on which action is based are wrapped in a fog of greater or lesser uncertainty.3

(2) Fog of war.

As the U.S. military fields more sophisticated equipment and doctrine it is likely that it will become more difficult to realize synchronized effects of MDO warfare at the brigade and below level. The Army now defines convergence, one of the key tenets of MDO as the realized synchronization of effects at multiple decisive points. The burden to understand MDO convergence and compete with precision will fall to all leaders and tactical operations centers. As units become more familiar with the MDO battlefield, leaders will likely become more competent in applying precise application of new tools and techniques – use of unmanned aerial systems to delivery fire support, cyber effects ahead of and in conjunction with ground maneuver, and movement to key terrain via multiple different delivery means – to name a few.

However, now, it is likely that units and leaders are not steeped in effective application of MDO effects. Largely because it is incredibly challenging to replicate an environment that simulates the MDO battlefield at the brigade and below level; it is a little easier at the Division level and above due to the digital transformation and availability of systems to replicate tactical operation center functions. However, at the Brigade and below level, where most of the unit is not yet connected to the digital common operational picture, situational awareness decreases, and it is challenging for Brigade and below tactical operations centers to generate shared understanding to the rest of the unit. The historical way to keep a flat common operational picture is the analog method. This will always be a necessary function, but it remains to be seen if it will be a sufficient means to provide effective situational awareness in an increasingly sophisticated battlefield. The effects of the “fog of war” are likely to increase as the total amount and sophistication of effects increases.

An example here is the type of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) aircraft overhead. Most conventional unit based junior leaders do not have access to the ISR feed or tracker that geolocates friendly aircraft locations. However, Brigade leadership entrusts junior leaders to take lethal action to negate the effects of enemy ISR. Field grade leaders must navigate the guiding principles of FM 3-0, authorities given during a given operation, and break down the constraints that units have already identified.

“Successful commanders are aware of the effects of cumulative risk over time, and therefore they continuously assess it throughout an operation.“4

(3) Risk management.

As commanders are “aware” of the cumulative risk, staff and field grade officers are responsible for being the receptor that consolidates, analyzes, and presents the risk to the commander. The temptation to “delay action while setting optimal conditions, waiting for perfect intelligence or achieving greater synchronization may end up posing a greater danger than swift acceptance of significant risk now”5 is a stiff threshold that many field grades struggle with.

Field grade key development positions are likely one of the first times that officers have access to a wider application of MDO effects and must consolidate them to inform a commander who must decide to “manage risk”. FM 3-0 proposes that contingency planning, the common operational picture, and use of commander’s critical information requirements (CCIR) are three tools from which commanders can buy down risk. Competency on these planning tools will likely enable field grade leaders to enable their commanders to apply the art of command.

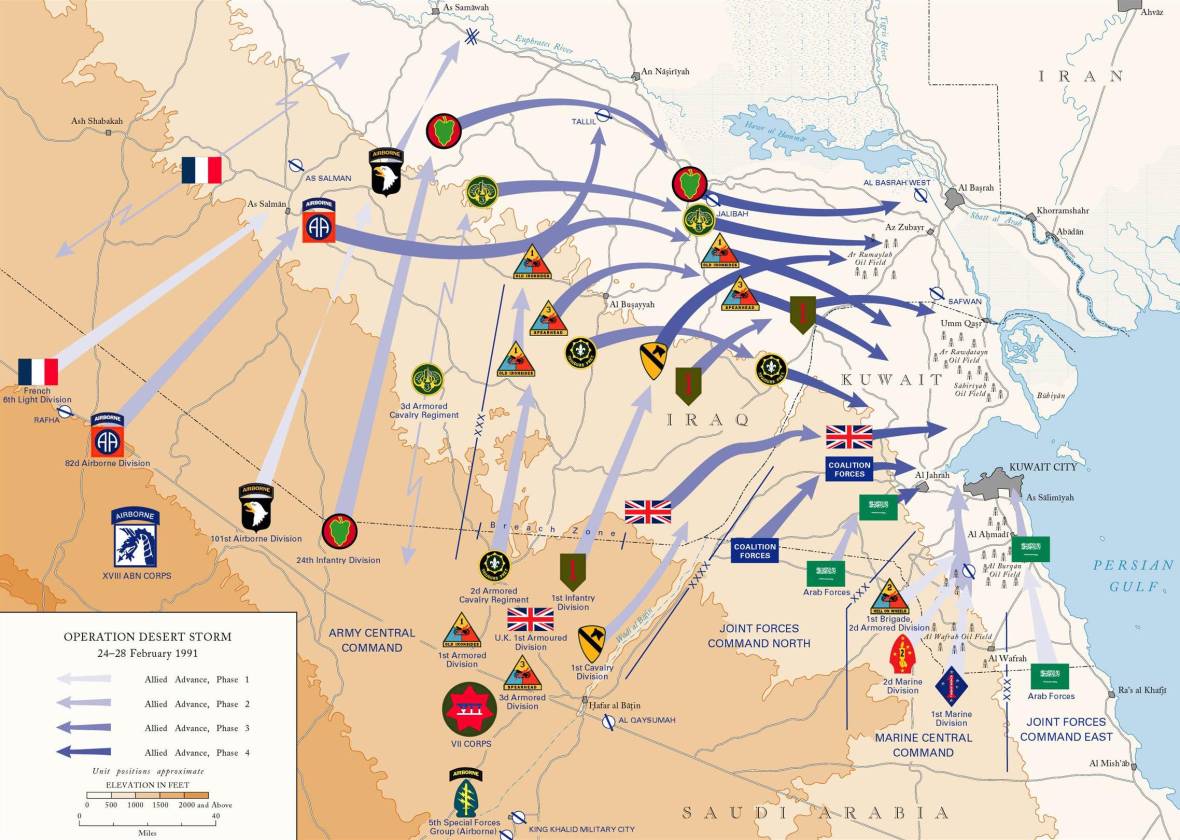

Here, Operation Desert Storm is illustrative. In January 1991, the U.S. was poised on the southern Iraqi border in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, patiently waiting for the ripe conditions to liberate Kuwait and confront the Iraqi Army that threatened regional sovereignty. At the time, amidst wide upgrades and fielding to U.S. military equipment, to include fighter aircraft and delivery munitions, the Joint Force codified Air Land Battle, which focused on bearing the effects of air power ahead of and in support of ground maneuver to seize key terrain. As many leadership memoirs describe and others reflect, air land battle was a decisive proving ground for U.S. military fighting doctrine. Air land battle proved to be successful in Operation Desert Storm as it only took ~100 hours of fighting and less than 30 days to achieve the objectives set forward. Although the doctrine was meant to be applied in defense of Europe amidst a Russian invasion, it still proved the forecasted progress. As leaders digest MDO doctrine, build competency across a wider set of tools, and practice implementation, leaders could benefit from observing the effects of MDO warfare across the hot conflicts rumble today and wargame the numerous potential cold conflicts that may spark in the future.The implications of the exposed challenges show that the competency gap looms in implementation of FM 3-0. As leaders prepare for key assignments and others take time to reflect on their current work, leaders should consider and be aware of the published doctrine, challenges leaders face, and techniques to close the gaps. Army University is a good starting point for time-crunched leaders seeking to expand their doctrinal reach!

About the Author:

Evan Bruccoleri is an active-duty Army Infantry officer serving as a Bradley Fellow at the Pentagon.

Opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not represent those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or any part of the U.S. government.

Endnotes:

- “Field Manual 3-0.” https://armypubs.army.mil/ProductMaps/PubForm/Details.aspx?PUB_ID=1025593. (accessed May 3rd, 2023), Para 1-9.

- Ibid., Para 1-10.

- Clausewitz, Carl von. On War, translated and edited by Michael Howard and Peter Paret. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988.

- “Field Manual 3-0.” https://armypubs.army.mil/ProductMaps/PubForm/Details.aspx?PUB_ID=1025593. (accessed May 3rd, 2023).

- Ibid